Technical Perspective: A Tale Of Two ISOs, Or What Water Resistance Ratings Really Mean

The International Organization for Standardization’s got it all down in black and white.

Originally published by on HODINKEE, November 28th 2017

One of the most perennially popular subjects for discussion on watch forums, at watch meet-ups, at trade shows, at watch shows, and indeed at any horological conclave you’d care to mention (real or virtual) is what depth ratings on watches really mean. You’ll hear all sorts of things – some say 100 meters is inadequate for anything but showering (to HODINKEE contributor and diver Jason Heaton, them’s fightin’ words), some say you should never shower with anything, even a dive watch, lest heat and soap do their devil’s work upon your gaskets, and pretty much everything in between.

However, as it turns out, there are fairly specific stipulations as to what the terms “Water Resistant” and “Diver’s Watch” actually mean, and it may come as a little bit of a surprise to learn that they’re not the same thing. In addition, that they’re regulated by two different standards – both of which are brought to you courtesy the good folks at the International Organization for Standardization, which has been reading the riot act to its audience of member nations since 1947. The overwhelming majority of the world’s nations are ISO compliant (162 as of this writing) and in a fractious, fragmented, fiercely fraught world, its edicts are the closest thing we seem to have, to having something everyone can agree on. Naturally, they’re headquartered in Geneva.

Now, if you know that watch depth ratings are regulated at all, then you probably already know that dive watch depth ratings, as well as testing methods, and a host of other dive-watch relevant characteristics, are regulated by ISO 6425. We talked a bit about what this particular ISO means in a roundabout way in a recent story on dive watch depth ratings and the takeaways from that story were fairly straightforward: 100 meter water resistance is actually more than adequate for recreational diving, and at least in the case of major players in the dive watch arena, the watches are tested well past their actual depth ratings (and in the case of Seiko there’s anecdotal evidence of their dive watches being significantly over-built – well beyond the rated specification.

The actual text of ISO 6425 is only available via purchasing a single-user license from the good folks at the International Organization, and while the general outline of its requirements are quite well covered in the Wikipedia article on dive watches, the ISO itself makes some interesting points.

The ISO defines a dive watch as any watch with at least a 100 meter depth rating, and which also has a “time pre-selecting device” – that is, either a digital timing device, or a rotating timing bezel; if the latter, it must be “protected against inadvertent rotation or wrong manipulation.” The scale must time up to 60 minutes and there must be (at least) five minute increments. In addition, the watch must fit the criteria for both antimagnetic and shock resistant watches, in compliance with the relevant ISOs (some of the requirements are quartz-watch specific, such as one that states there must be a battery end-of-life indicator, but we’ll focus on the specs for mechanical watches). There is also a “thermal shock” test, during which the watch is immersed successively in 40ºC, 5ºC, and 40ºC water (ten minutes each) and then tested for water resistance. It’s probably not a coincidence, by the way, that 40ºC is the maximum recommended safe temperature for a hot tub, so if you’re wearing an ISO 6425 compliant dive watch, you may (apparently) hot-tub with abandon.

The actual test for water resistance is the so-called “condensation test.” The procedure is simple: the watch is placed on a plate and heated to between 40ºC and 45ºC and then a drop of water at 18ºC to 25ºC is placed on the glass. If this produces condensation on the underside of the crystal, it’s a fail. (You can get a false positive if the watch was assembled under humid conditions, although I suspect that in a modern, climate-controlled assembly facility, this is a non-issue; certainly this is the case for both Rolex and Seiko.)

This test obviously avoids destructive testing. There are two distinct “overpressure” tests: one at a minimum of 10 bar for two hours, and an additional test for security of the crown, in which a five newton downward force is applied to the crown for ten minutes, at 10 bar. There’s also a third test, which involves immersion in water to a depth of 30cm for 50 hours, to be followed by the condensation test, as well as a 24 hour salt-water immersion test (this is a test for resistance to corrosion, rather than water overpressure resistance).

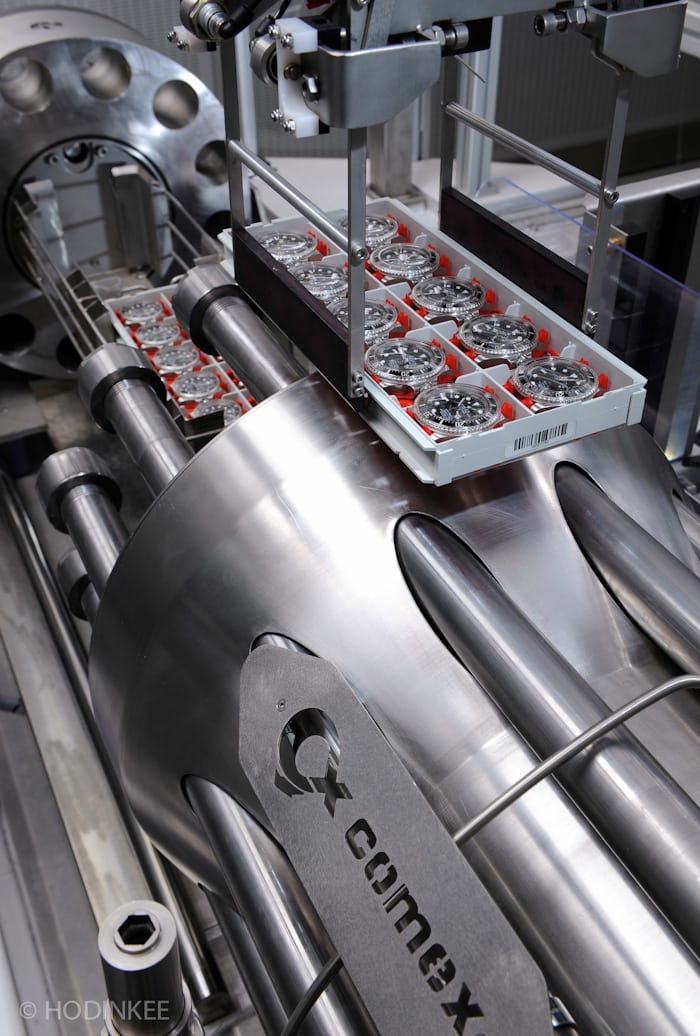

Now the big question here is this: is every individual watch subjected to each of these tests? The ISO only requires testing of every dive watch for the two hour overpressure test; if you are a maker of diver’s watches in an ISO-compliant country, every watch you label a “diver’s watch” has to be subjected to this test. The other tests may be done according to the regulations for “type testing” – essentially, you test a sampling of the total production run; what fraction is determined by the size of the run, and the specifications for type testing. Natch, there’s an ISO for that too: ISO 28590, and if you think ISO 6425 makes, haha, dry reading, may I recommend the stupor inducing minutiae of “Sampling Procedures For Inspection By Attributes – Introduction To The ISO 2859 Series Of Standards For Sampling For Inspection By Attributes.” Joking aside, this ISO is actually pretty sophisticated; it and its series of related ISOs provide fairly strict guidelines to ensure statistically significant sampling across a range of possible production numbers, and is specifically designed to protect the consumer and put the onus of demonstrated reliability on the manufacturer, so go, go ISO.

Obviously not every watch with a water resistance rating is a diver’s watch per se. Watches that are not diver’s watches are actually regulated by a completely separate ISO, which is International Standard ISO 22810 Horology–Water Resistant Watches, the most current revision of which, in 2010, was such a source of pride to the Organization that it actually induced them to make a feeble pun. (The ISO had not been revised since 1990.) Though much online discussion of water resistance seems to focus on ISO 6425, ISO 22810 actually covers a far greater range of watches and is arguably more relevant to the general consumer, than the specialist requirements of the dive watch ISO.

There are a number of quite significant differences between the two ISOs. Because its scope is so broad, ISO 22810 defines no minimum standard for water resistance; instead, it presents testing criteria for the widest possible practical range for non-dive watches, and also makes it the manufacturer’s responsibility for stating “warranty conditions and precautions to be taken to maintain the quality of the watch over an extended period of time.” Rather than requiring any tests, it provides testing procedures which it is then the manufacturer’s responsibility to define at the production stage “if he wishes to be able to guarantee that they satisfy the requirements of the International Standard.” The maker is free to have whatever testing methods they prefer, but whatever those are, they must provide a level of guarantee of water resistance, such that any watch labeled water resistant can pass the enumerated tests.

According to the Organization, the newly revised ISO is intended to ensure that if, for instance, a watch has a 30 meter water resistance, the watch is then suitable for any and all “aquatic activities” of any kind, up to 30 meters’ depth – irrespective of the manufacturer. In practice this should mean that while your 50 meter water resistant watch isn’t a dive watch per se, that if you do dive with it to, say, 20 meters, it shouldn’t spring a leak – on the assumption that its date of manufacture is after the ISO went into effect, of course.

All that said, any water resistant watch must be manufactured, and tested by the maker, so that in use it conforms to the following requirements.

First, there must be no condensation on the inside of the glass, per the condensation test, after the overpressure test. Significantly, the actual overpressure is here defined by the maker; that is, no 100 meter minimum; you can test a watch to as little as 2 bar for 10 minutes (more is fine of course, depending on the watch). The immersion test is also less stringent than for dive watches: 10cm depth, for a minimum of one hour. The thermal shock test is similar but not identical: 40ºC for five minutes, 20ºC for five minutes, and 40ºC for five minutes, to be followed by the condensation test. The 5 newton pressure-on-the-crown test is for five rather than ten minutes; there is no requirement for salt-water corrosion resistance, nor is there any for shock resistance, or resistance to magnetism. So clearly just on the basis of requirements, a diver’s watch must, overall, be a lot tougher than a non-diver’s watch. If a manufacturer wishes, watches can be tested using air overpressure rather than actual immersion, which avoids the risk of possible destructive damage to the tested watch (probably a nice caveat if the watch you are testing is a $30,000 Vacheron dress watch).

From an owner’s perspective probably the most significant difference is this: if you buy an ISO 6425 compliant diver’s watch, you know your watch – your specific watch – has been tested for overpressure resistance; you also know that the model is sample tested during production to ensure compliance with a host of other requirements. For “water resistant” watches, on the other hand, no test frequency stipulations are made at all – this is left up to the manufacturer’s discretion and one assumes that sample testing would be the rule in such a case. More stringent testing is always possible – for instance if you buy a Montblanc watch with a 500 hour quality certification, your specific watch has been individually tested with both an air and water overpressure test to a minimum of 3 bar water resistance; therefore while generalizations can be made, you’re wisest to take manufacturer specifications and testing into account, if that information’s available.

The water resistance ISO closes with some advice to owners:

- test for water resistance every time the case is opened

- make sure you’ve got the right strap/bracelet for the job

- avoid sudden temperature variations

- avoid banging it around (I’m paraphrasing)

- don’t operate the crown/pushers underwater

- make sure you replace the crown/pushers after using them (in other words don’t go swimming with the crown pulled out)

- rinse after salt water immersion

Now, the most important thing to bear in mind after all’s said and done is that a watch is only as good as its gaskets, and if you have a water resistant, or diver’s watch, that’s a few years out or more from its last service, you’re increasingly in less secure territory. Also it’s worth bearing in mind that the water resistance requirements are current as of 2010, so anything earlier than that was not made under those specs. Finally, you’ll note that absolutely nowhere is there any mention of the (in)famous “dynamic pressure” issue; the Organization says that for example, a 30 meter water resistant watch is suitable for any aquatic activity up to thirty meters, which presumably includes SCUBA, water polo, and underwater air guitar competitions for all I know. So be safe, get wet, and don’t forget to keep your crown screwed down.

Get More Articles Like This in Your Inbox

We're constantly creating great content like this. So, why not get it delivered directly to your inbox? By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy but you can unsubscribe at any time.