Why No Watch Is ‘Waterproof’

“You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.” – The Federal Trade Commission, 1960

One of the (many) pet peeves of the self-described watch enthusiast is the amount of verbiage on modern watches, although this is not particularly a feature of only modern watches – I suppose in the days when automatic winding systems were fairly novel, having that feature called out on the dial of a watch would help it stand out from the crowd in a jeweler’s display case. Descriptive verbiage seems to very much be a phenomenon associated with wristwatches rather than pocket watches, which as a rule carried little or no such information on their dials or cases. But as wristwatches gradually displaced pocket watches and began to dramatically diversify in functionality and purpose, words crept gradually onto watch dials, and as well, watch cases, with greater and greater frequency.

“Water resistant”

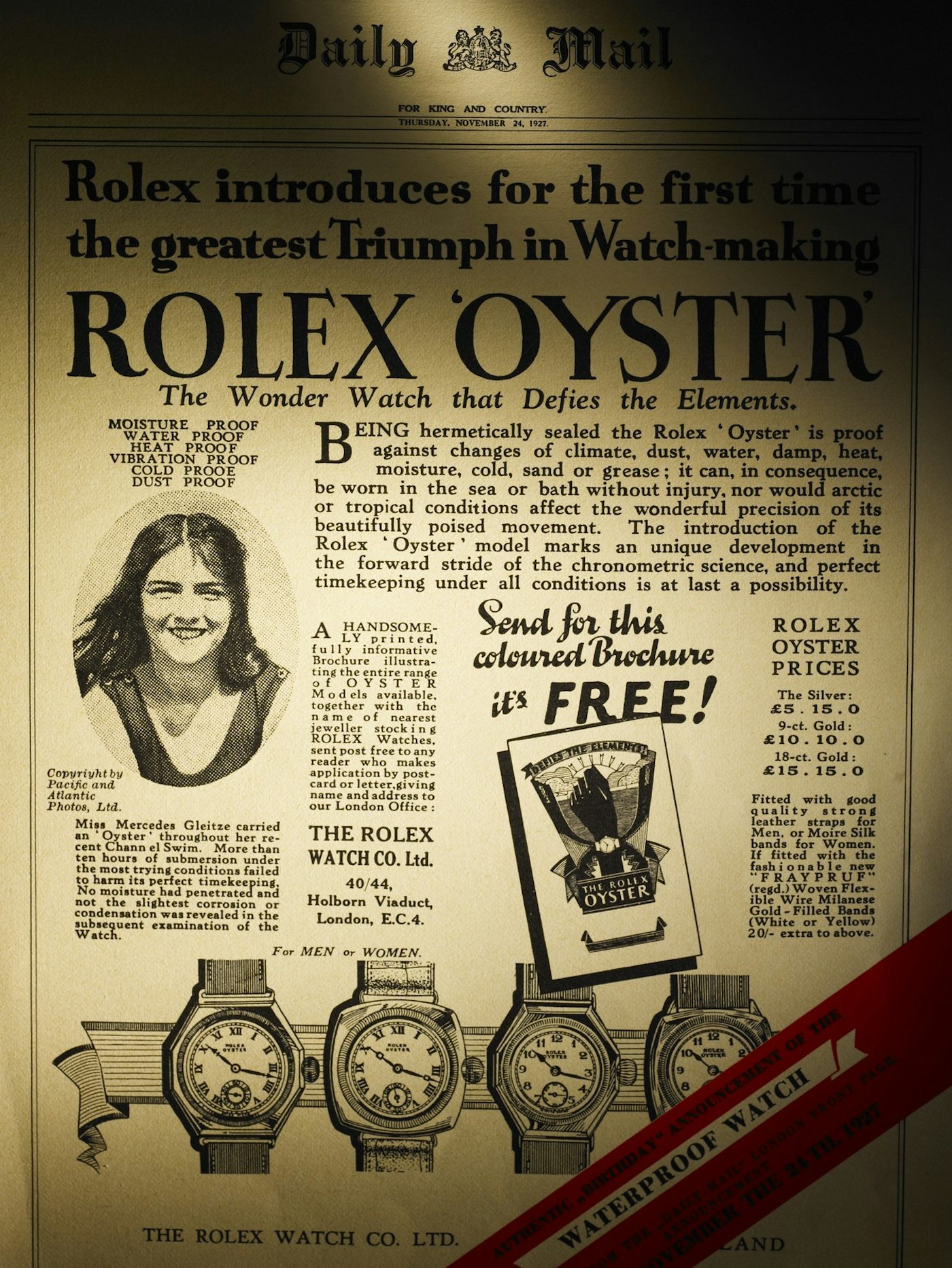

One word which used to appear quite often is “waterproof,” and naturally, the term appeared in advertisements as well – and why not? Who wouldn’t want a watch that’s waterproof, after all? Water is the single greatest enemy of watchmaking. If water gets into a watch case, it will, first of all, take its own sweet time about getting out, and as many mission-critical parts are made of materials which will quickly and cheerfully corrode if moistened, keeping water out, to the extent that it is possible, is surely a useful feature and one well worth advertising to boot. Not only that, but aitch two oh will also play hob with the finish of watch dials, and many an older watch bears upon its face the blemishes wrought not just by time, but by the Universal Solvent as well.

Now, if you begin to spend much time around watches and vintage watches, at some point, you are apt to notice that the word “waterproof” is present on some watches but not on others, and it may occur to you to wonder why it is that some watches boast of waterproofness, while others more circumspectly simply say “water resistant” – often with the latter qualified in terms of the meters or feet of immersion to which the watch can be expected to remain uninjured. The whole history of waterproof and water resistant watches, by the way, is a long and most interesting one, and it goes back quite a lot further than many of us might suspect – water having been regarded with enmity by watchmakers and watch owners for probably as long as there have been watches (and clocks; many early verge clocks had iron movements, and the centuries have done their destructive work in quite a few cases; there are several fascinating accounts online of the development of early waterproof watches, including this one).

Claims of “proofness,” of course, are not absolute – or you would think they would be understood not to be, but one should never underestimate the ability of the General Public to misinterpret, nor the desire of watch advertisers to attempt to create an aura of invulnerability for their products. Water proof, after all, is not strictly speaking a term that allows for any exceptions – it just means that the watch is, well, proof against water, and with no further qualifications, the reader of an advertisement boasting of waterproofness, and seeing the term on a case or dial, would be apt to possibly overestimate the water resistance of a watch, with potentially serious consequences. Watch manufacturers and dealers nonetheless cheerfully used the term with impunity until, in the United States, the Federal Trade Commission got involved, in 1960 (it may have been even earlier, but the oldest archived FTC guidelines for the watch industry I have been able to find date from that year).

The FTC’s action to try to at least put some guardrails in place in terms of truth in advertising was intended to clarify to the sometimes possibly literal-minded readers of ads that what they were told they were getting, was not necessarily what they might have thought they were getting. Specifically, the FTC was responding to stated guarantees in watch advertising which offered “guaranteed” waterproofness, as well as shock proofness, proofness against magnetism, and so on.

The guidelines were applicable, naturally, only to the U.S. market. However, the point seems to have been taken by the watch industry as a whole, and the term “waterproof” gradually began to fall out of favor in the 1960s, to be replaced with the term “water resistant,” and often with a statement of the specific depth to which static testing had indicated that resistance could be relied on. Today, every watch enthusiast probably knows the designations for the standards by heart: ISO 2281, for “water resistant” watches, and the accompanying, more rigorous ISO 6425, for diver’s watches. The industry-wide adoption of these standards so thoroughly substituted for the term “waterproof” that it simply became extinct, which is why you will search in vain today for an advertisement boast that a watch is waterproof.

Or will you? The FTC issued a decision in 1999, rescinding the watch guidelines as no longer relevant, citing the international standards and the widespread, indeed virtually universal, adherence to them. Absent any guidelines from the FTC, however, the term seems to be creeping back, at least in some quarters. Oddly enough, the term as applied to watches has seen something of a resurrection in the consumer electronics press – thanks in part to the development of smartwatches like the Apple Watch and fitness trackers, which bring the question of water resistance of a wristwatch to a whole generation of consumers who might never have thought to wonder about it before. The term still seems to resist being reborn in the domain of mechanical watches, however, and this despite the fact that water proofness, thanks to many decades of technical improvements, could be claimed now for a mechanical watch (especially a dive watch) more plausibly than ever before. Perhaps it will make a comeback there as well, however – the charm of promised perfection may prove too great to ignore.

For more on water resistance and the international standards, check out “What Dive Watch Depth Ratings Really Mean,” right here on HODINKEE. And take a look at that time we put two antimagnetic watches to the test, with an absurdly powerful magnet.

Get More Articles Like This in Your Inbox

We're constantly creating great content like this. So, why not get it delivered directly to your inbox? By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy but you can unsubscribe at any time.