Inside The Manufacture: Going Where Few Have Gone Before – Inside All Four Rolex Manufacturing Facilities

For the first time, we go inside all of Rolex’s factories in Switzerland, and what we found amazed us.

I will begin this detailed article with a wholly unsurprising admission. I love Rolex. I own more of them than any other watch from any other manufacturer, and I have always believed its contribution to watchmaking is beyond measure. But, I have another admission. Of the handful of Rolex watches I own, the youngest dates to 1976 – making it, in fact, older than I am.

There is and was a distinct difference between the Rolex of today and the Rolex of yesterday, and I don’t think it would come as a surprise to anyone if I said I preferred that of yesterday. But, that doesn’t mean I don’t have great respect for the Rolex of today, nor would it prevent me from encouraging family, friends, and readers to look to the Crown for a new watch today. When my only sister gave birth to her first son, my first nephew, I purchased him a brand new Rolex and engraved his initials on the back. He will get it the day he turns 18 (or 25, depending on how moody he is at 18) after years of wear by his mother. It will, I can guarantee, still work flawlessly, and look even better. And that’s indisputably the most wonderful thing about a Rolex from my own perspective – they are unbelievably accurate, incredibly cool, and supremely lasting.

In this special HODINKEE feature of Inside The Manufacture, I will recount a four day experience that completely changed my perspective on the world’s most important watch maker – the time that I got to spend inside all four of Rolex’s actual production facilities in Switzerland. I had many ideas about what I would see, and while some were accurate, others could not have been further from the truth. Below, you’ll hear and see what it is like to go inside Rolex in a way that few have, or will ever get to experience.

A (Brief) History Of Rolex

Rolex is one of the few watch manufactures that has two completely separate but totally equal strengths – an amazing history of innovation, in really meaningful watchmaking; and world-class manufacturing capabilities today. In a way, they go hand in hand, and while many within the industry know why and how Rolex became Rolex, I feel we should cover a few of the basics for a broader audience.

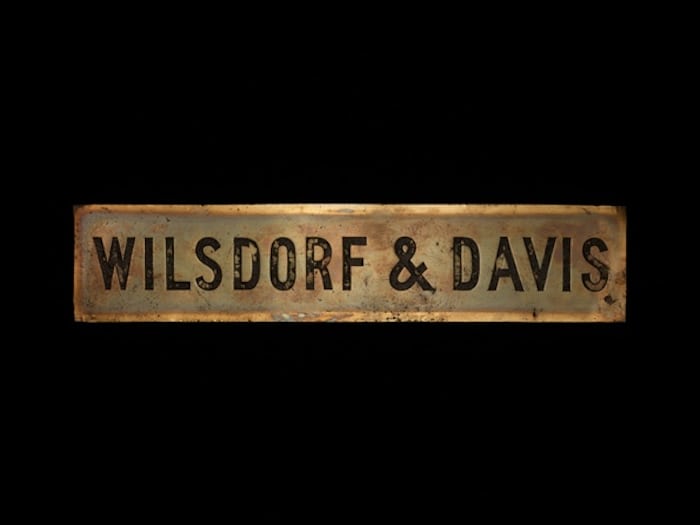

Hans Wilsdorf was born in in Bavaria in 1881, but would become fascinated by English culture. In 1905, Wilsdorf created “Wilsdorf & Davis,” specializing in the distribution of wristwatches in the United Kingdom (this at a time when watches sold were overwhelmingly pocket watches). One of his suppliers, the Aegler company of Bienne, specialized in the manufacturing of small, precise movements required for a wristwatch – not a common thing back then at all – and would actually become Montres Rolex, SA down the road. Back then, though, Aegler supplied movements to many other companies, including Gruen.

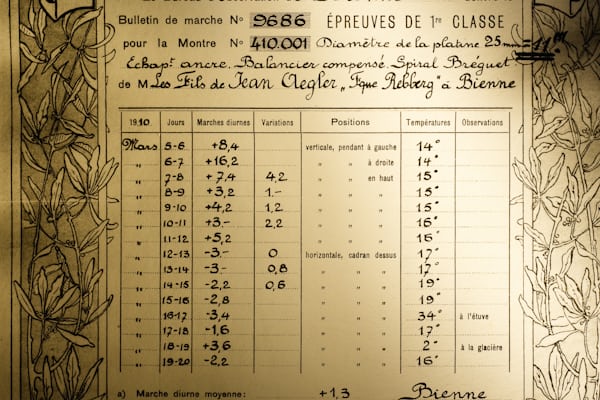

Wilsdorf was obsessive, and the very first target he set his eyes on was chronometric performance – but for a wristwatch. Up until this point, the most accurate watches in the world were pocket watches because, few were paying much attention to wristwatches. Wilsdorf changed all that when he submitted one of this Aegler-powered watches to the Official Watch Rating Center in Bienne, Switzerland – something of a predecessor to COSC – in 1910. The watch passed all tests, and was the very first wristwatch to be awarded this certificate.

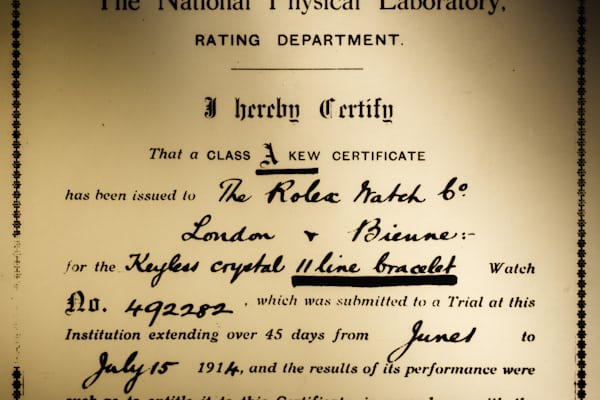

You can see a copy of this document above, and you’ll notice that the manufacture name is not Wilsdorf, but Aegler, though it was housed in a Wilsdorf & Davis watch. Then, in 1914, Wilsdorf submitted another wristwatch to the Kew observatory in the United Kingdom. Kew, relative to even its Swiss and French counterparts, conducted the most stringent accuracy tests on watches in the world. For example, while most tests were conducted over fifteen days, Kew tested watches for 44 days, in several positions and temperatures.

Kew was, among other things, responsible for testing marine chronometers for the British Navy before sending them to vessels going to sea. Let’s remember that at this point, there was no such thing as GPS or digital technology, and a marine chronometer was nothing short of absolutely vital to navigation. The Rolex watch (Wilsdorf adopted the “Rolex” name in 1908 because it was short, easy to pronounce in any language, memorable, and possible to inscribe elegantly on both the dial and movement of watch) performed exceptionally well when tested, and was award the “A” certificate by Kew. This Rolex was the very first wristwatch in the world to achieve such performance – up until this point only true Marine Chronometers had been worthy of the mark.

Let’s get into a quick little aside about around the Kew A certificate you saw above. We know that Wilsdorf submitted the one watch to Kew in 1914, and it received an observatory chronometer grade. What does that mean? It means that this watch operates on a completely different plane than a traditional mechanical watch. Its precision and accuracy are exemplary. Max Studer, the former technical director of Patek Philippe had this to say:

“An Observatory Chronometer Is To Watches What A Formula One Engine Is To Cars”

– – MAX STUDER, FORMER TECHNICAL DIRECTOR OF PATEK PHILIPPE

Observatory Chronometers represent a special place in watchmaking, and indeed represent a special place in the mind of collectors. Consider the fact that a Patek Philippe reference 570 in platinum (the 570 is the archetypal vintage Calatrava, and very rare in platinum) would sell for around $100,000 these days (one here at the Patek 175 sale in November 2014 at $96,000), while a platinum observatory chronometer wristwatch, like, say the JB Champion piece, would, and did, sell well into the millions. Not only are observatory chronometer wristwatches incredibly accurate, they’re also extremely rare.

But, back to Rolex. The 1914 piece was not the only wristwatch movement that Rolex sent to the Kew Observatory – there were approximately 145 Rolex calibers produced that could meet Kew A standards; 136 did, and received certification. This information comes from research first presented in James Dowling’s Unauthorized History of Rolex. According to Paul Boutros (whom I now believe to be the most knowledgeable man there is in regards to these Kew A Rolexes) just 24 were cased, into full size (34 mm) gold watches, all in 1952. Only 24. So not only do these Kew A certified watches have the observatory certified movements, they are also among the rarest Rolex watches around. Paul himself owns one, and he considers it one of the finest and most special watches in his collection.

You can see that even the movement of these watches (Reference 6063) is marked “KEW A TESTED.” So there are 24 of these full size watches in gold out there, and you simply never see them come up for sale. The last time one came up at auction, it was 2009 and it sold for $50,000. James Dowling is offering a gold Kew A watch on his website now, though the dial has been refinished. If this is a watch that interests you, I would hold out and try to find one with an original dial – though you will likely be waiting a long, long time.

Still, let’s not forget that there are 112 Oyster watches in steel (boys size – 28 mm) with Kew A tested movements out there! These watches look like your average Speedking, but have a dial that will say “Kew A” Certificate at 6 o’clock. The watches are tiny and don’t look like much, so they sell for very low prices when they do come up for sale. Keep an eye out, and if you’re okay with the small size, you could have a very special watch for not much money. This one at Bonhams London sold for less than £3,000 in November 2013.

My final note on the Kew A watches is that what makes these watches, unlike most Rolexes, is not the dial but the movement, in particular the escapement with Guillaume balance wheel (a special type of very precise compensating balance.) These watches, in steel or gold, have no shock protection and many have broken over time, causing the escapement to be replaced. Without the very special Observatory-grade escapement and Guillaume balance, the charm of the Kew A is lost. It would be akin to buying a late 1960s Reference 1680 Submariner with a replacement white Submariner dial. Be very careful in buying these, and for more information I can not recommend Paul Boutros’ 2006 post on the subject enough.

An example of the first Rolex Oyster watch, from 1926

By 1920, Wilsdorf had moved Rolex to Geneva not only to be closer to all of his suppliers, but also because he, even then, recognized that Geneva held a special place in the minds of watch consumers. Montres Rolex S.A. was officially formed and it was then that the Rolex we know today really began to take shape. Not only had Wilsdorf been effective in producing highly precise calibers small enough for the wrist, but his attention was now also set on taking the watch to sport by making it waterproof. Why? Becuse while the pocket watch was indeed used for sport, it was always used on the sidelines. The wristwatch, Wilsdorf saw, could and should be used not by only a spectator, but also by a participant.

To do this, Wilsdorf created the “Oyster” case, which launched in 1926 to much fanfare. The Oyster, which would truly revolutionize the wristwatch, now featured a screw-down case back, bezel, and crown, and the watch was as water-resistant as one had ever been. A little known fact is that the fluted nature of the bezel that has become something of a Rolex trademark was indeed first created to serve a purpose – the ridged nature allowed the bezel to be tightly screwed into those early oyster cases. The bezel of a Royal oyster is no longer screwed into the mid-case, but we still see fluted bezels on several of Rolex’s most iconic designs.

While Rolex’s manufacturing and design capabilities were (and still are) the reason that this company is so respected by its peers, it was Wilsdorf’s knack for storytelling that would would elevate Rolex to become the archetype of the luxury wristwatch not only for those within Switzerland, but also all over the world.

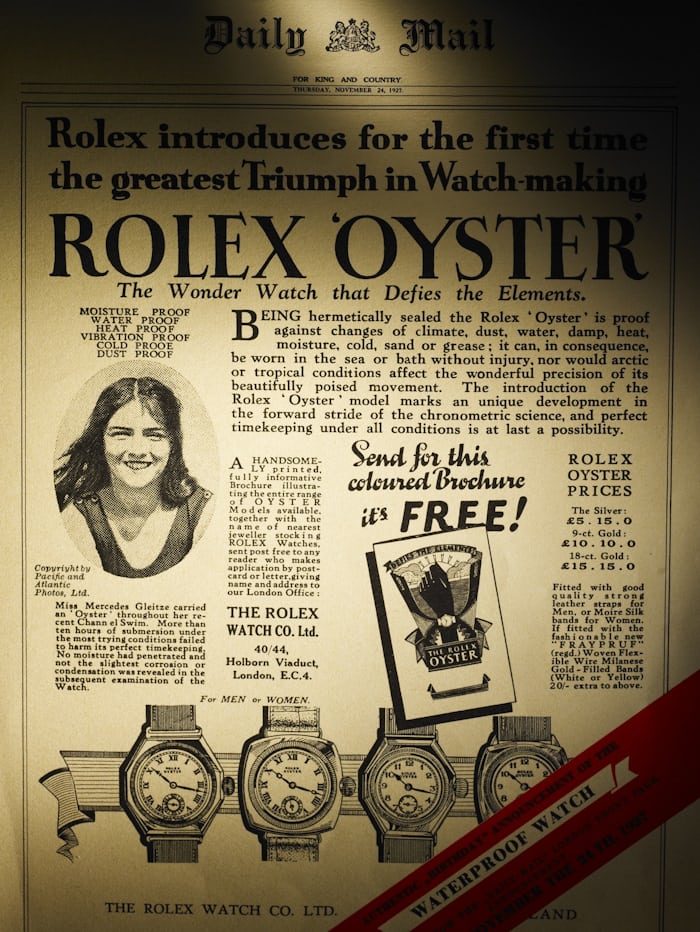

In 1927, Wilsdorf heard of a woman British woman named Mercedes Gleitze who had successfully swum the English Channel. Wilsdorf asked Gleitze to wear a Rolex Oyster watch around her neck as she swam. It should be noted that Gleitze had attempted this feat seven times before making it successfully, and then, due an attempt by another woman to steal the spotlight, was asked to swim it again. It was this last time that Gleitze wore the Rolex Oyster, not on her wrist but around her neck.

She didn’t make it. After 10 hours in the freezing water, she was forced to abandon the attempt and be pulled into her trainer’s boat, because of numbness in her extremities. It didn’t matter, and Wilsdorf ran an ad in London’s Daily Mail citing not this most recent attempt, but Gleitze’s earlier successful attempt (which, of course, she swam without a Rolex). Still, her Oyster did withstand up to 10 hours in the bitter cold water of the English Channel, which was no small feat (you can read a detailed account here).

In spite of Gleitze’s failed attempt in the so-called “vindication swim,” Wilsdorf’s advertisements made the typist a celebrity. She would be used in Rolex advertisements for years, and she was, in the eyes of many, the very first Rolex brand ambassador and one of the earliest and most successful brand ambassadors in general, in the modern sense. This is, quite simply, one of the most important partnerships in not only Rolex history, but also all of watchmaking, and even consumer products overall. We would see Wilsdorf adopt this model from Gleitze forward, in the conquering of not only the sea, but also the land and air.

The third tenet of Wilsdorf’s master plan to make the most versatile, sellable watch on the planet was to make one that would power itself. Rolex would not be the first to make an automatic watch, but it wasn’t the first to make a waterproof case, either. In the same way that Apple is seldom first to launch a product, Rolex would observe, study, and improve. For example, have you ever heard of Harwood? Probably not. John Harwood actually patented the self-winding watch some years before Rolex did – 1924 vs. 1931 – but let’s just say the Harwood brand hasn’t enjoyed the same success as Rolex. The difference between Harwood’s concept and the Oyster Perpetual was that Harwood’s idea was to use a “hammer” winding system, while Rolex’s system would use a weighted rotor turning through a full circle. Needless to say, Rolex’s invention has gone on to become the industry standard – just another reason why Rolex is Rolex.

Rolex continued to innovate through the middle of the century with the introduction of both the Datejust in 1945, which was the very first wrist chonometer to feature the date of the month not on the dial but in a window, and the Day-Date in 1956, which was the first wristwatch to show both the day and date on the dial. They are now two of the most imitated watches on Earth.

Professional Watches

Up until this point, Rolex had created watches that can be worn every day without much fuss or attention. But it is with 1953’s Submariner that we see an entirely new type of Rolex, a type that will come to define not only its own brand, but also, one could argue, watches in general – the “Professional” watch. These are the watches that millions have since adopted as part of their every day outfit – including the Submariner, GMT-Master, Cosmograph Daytona, Explorer, and Milgauss.

It’s hard to find the proper adjectives to describe the Submariner. It’s a watch that can both begin and end a collection. It’s awatch that you can wear every single day of your life and not worry about, or it’s the watch you can put in a safe and have it rise in value year after year. The Submariner is, in my belief, the quintessential timepiece for many. In the countless discussions I’ve shared with my colleague Eric Wind, one remark stands out.

“When my mind thinks of the word ‘watch,’ it is a Submariner I see.”

– – ERIC WIND, HODINKEE CONTRIBUTOR

The Sub has taken on a larger persona than other dive watches, even those with amazing history to boast of in their own right, like the Fifty Fathoms (which, as many know, actually pre-dated the Submariner by one Baselworld) or Omega’s Seamaster. The Submariner series began with the reference 6204, water resistant to 100 meters. It featured a small crown, which would later be replaced by an 8 mm crown that would become a collector icon.

Today’s Submariner – equipped with crown guards for over the last half-century – remains one of the most robust all-purpose watches on the planet. You can read more about the Submariner here.

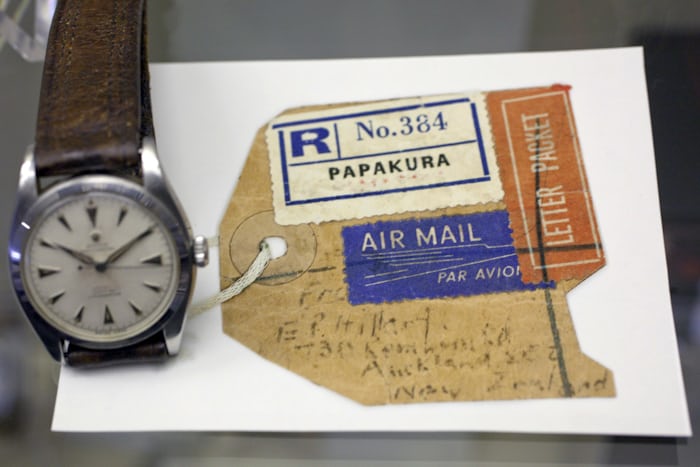

While the watch above doesn’t look like what many of us think of as an Explorer, or even say “Explorer” on the dial, it is the patriarch of the line. The story goes that Sir Edmund Hillary brought with him an Explorer as he summited Everest for the first time – however that is only half true. He did indeed wear a Rolex, but it was this watch, which we saw on display in the Beyer Museum. It’s not an Explorer exactly, but something that would help define what an Explorer would become.

A true Rolex Explorer of both yesterday and today is defined by a black dial with a large triangle at 12. The dial is marked with dashes except for at 3, 6, and 9, where you see Arabic numerals. Below is a rare reference 6610 with tropical dial, though most collectors tend to think of the 1016, which came immediately after, as the archetype for the Explorer.

The Explorer today is slightly larger at 39 mm, but retains many of the same characteristics of the original. The Explorer is, in my belief, the underdog of the Rolex tool-watch collection but truly the most versatile, as its smaller size allows it to be dressed up with a nice strap. On a personal note, an Explorer 14270 was my very first Rolex ever.

The easiest story to tell of any of the Rolex tool watches is that of the GMT-Master because it, like many of the watches mentioned above, truly created a category, and still defines it today. The GMT-Master was the first watch to use a 24-hour hand, along with a 24-hour bezel, to indicate a second timezone. Developed for the first transcontinental airline pilots, the relationship between the GMT-Master and PAN-AM is well documented. Considered to be the watch of the original jet-set, the GMT-master is perhaps best defined not by the earliest reference (the 6542 seen above), but by the 1675 – where it gained both crown guards, and an aluminum bezel. Today, the “Pepsi” bezel that most associate with the GMT-Master is only available on the white gold model, while the steel model features a black-and-blue bezel.

One of the most overlooked Rolex sport watches is the Milgauss. Created to be worn by scientists and technicians at CERN (the European Center for Nuclear Research, which today is home to the Large Hadron Collider) and elsewhere, the Milgauss was one of the first mainstream watches with anti-magnetic properties. It was not a commercial success at all and languished in jewelers’ display cases for years before it was revived in the mid-2000’s to much fanfare.

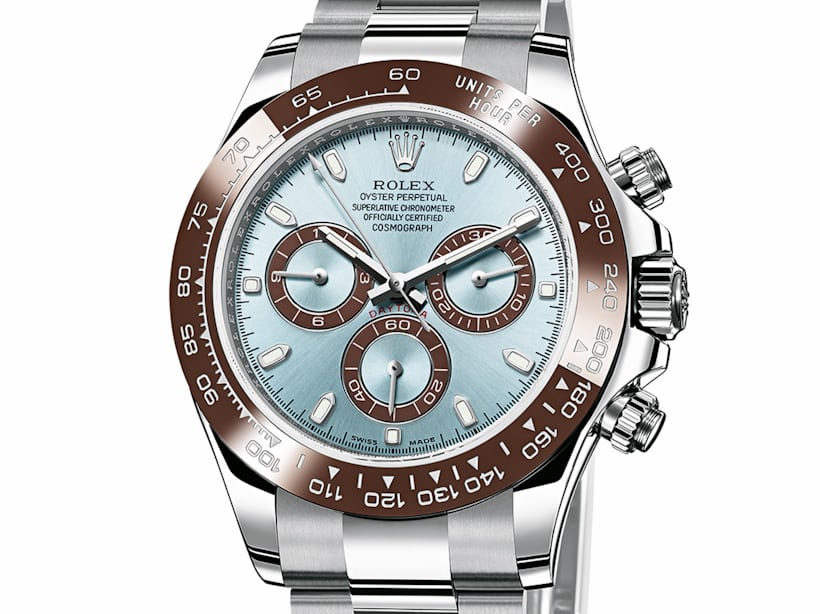

The very first Rolex Daytona reference 6239 hit shelves in 1963, and I won’t spend a tremendous amount of time on this because I have already written a fairly exhaustive (and exhausting) look at the earliest Daytona. Further, perhaps the most well known and sought after version of the Daytona is the “Paul Newman,” which also was the subject of one of our Reference Points features here. The Rolex Daytona now features an excellent in-house, self-winding, column-wheel chronograph caliber that I’ll dive into more below.

The Sea-Dweller holds a special place in the minds and hearts of real divers. Launched in 1967 with the guidance of professional divers, the Sea-Dweller remains a watch that few have a need for, but many desire; it’s become an icon in its own right, because of just how far Rolex has taken the engineering of the dive watch. The Sea-Dweller is still made today, with a model rated to an amazing 4,000 feet.

The Explorer II followed up the pure elegance of the Explorer I with a true period piece. It had a fixed 24-hour bezel and bright-orange hour hand. Neither the hand nor the bezel were adjustable, so it simply providing its wearer with military time. The watch was, as the story goes, designed for speleologists, who, working in caves, would find it impossible to distinguish night from day. It, like the Milgauss, was not a commercial success at first, although it began to be enthusiastically sought by collectors in the ’90s. The Explorer II is still made today, and the orange hand was brought back to production in 2011.

The Post-Wilsdorf Era

When Hans Wilsdorf died in 1960, he left the ownership of Rolex to the non-profit organization he created in 1945 – the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation. The Foundation is still around and its members still retain 100% ownership of this multi-billion dollar company. They are, very quietly, one of the largest charitable organizations in Europe.

Following Wilsdorf’s passing, Andre Heiniger took the helm of Rolex, followed in 1992 by his son Patrick. It was under his guidance that Rolex became the completely vertically integrated master of quality that it is today. Twenty-seven facilities became four. Rolex began acquiring every supplier they could – including legendary bracelet maker Gay Freres. The completely informal arrangement between Rolex Bienne and Rolex Geneva would be formalized when the Wilsdorf Foundation acquired the ownership of Bienne from the Borel family which happened much more recently than you might think: Rolex Geneva didn’t purchase Bienne until 2004, for over CHF 1 billion.

“Though owned by completely separate entities, Rolex Bienne And Rolex Geneva worked together exclusively for over 70 years, based on nothing more than a handshake.”

It is interesting to note that in Jack Heuer’s biography, the patriarch and modern leader of Heuer (now TAG Heuer) tells of a time when his company was in trouble and Mr. Borel, the owner of Rolex Bienne, sought to acquire Heuer. It was Mr. Heiniger who didn’t see the future Rolex using Heuer’s electronics business. Heuer further revealed that Rolex Bienne actually acquired almost 50% of his company when it went public in the late ’60s – imagine if this acquistion had been approved by Heiniger back then. Rolex and Heuer could have been joined forces and today the competitive landscape would be very different!

Patrick Heiniger’s initiative to control the entire production process of Rolex, has left the company today with four main facilities, and it is these four absolutely state-of-the-art locations to which I was invited.

By the time I received the invitation from Rolex Geneva to visit its four facilities, I had been to just about every other factory one could imagine – ranging from those who are simply packaging up pre-made movements and strapping them into off the shelf cases and dials, to those who are still doing everything by hand (but only producing a few watches per year). What I saw within the halls of Rolex wasn’t like either; it was like seeing something brand new being made, something that went beyond a watch. The scale of everything, the detail, the people and perfection, is I think unique in watchmaking, if not all consumer products. I will say that all photos below have been provided by Rolex – I was not allowed to take my own. While I certainly would’ve liked to shoot my own, I do understand and respect the decision. After all, Rolex has more to lose than anyone in terms of quality and production knowledge.

The facility that is most associated with Rolex is Les Acacias (it’s situated across the Arve River from Geneva). This building serves as its international headquarters and houses all senior executives, as well as the heritage department (yes, there absolutely is one; and no, I absolutely did not get to go inside) and is the final point in the Rolex watch production line. It is in Les Acacias that all marketing, communications, design, research, and development takes place – it is the hub of Rolex. It also houses Tudor’s headquarters.

Inaugurated in 1965 and updated in 2002 and 2006, Rolex HQ consists of two 10-floor production units. It is the only of the four Rolex facilities that features a façade in the trademark Rolex green. From a manufacturing standpoint, the work being done here consists of final assembly, along with several stages of final quality control.

It was here that I first realized just how wrong my – and many of my peers’ – preconceptions were about Rolex. I had been told by several watch industry insiders, including presidents at very well known brands, that Rolex produces watches completely devoid of the human touch. As soon as I stepped into the watchmaking room, I knew just how very wrong we all were.

There are people everywhere. And I mean every where. Dozens of assemblymen and women line the absolutely pristine rooms, each working with a dedicated purpose. Actually, these rooms are more than pristine – they are called “Controlled Environment Zones” and are totally dust and humidity free. Here the watch will see the last 10 or so steps of assembly. This includes placing many of the components from the other three facilities into the watch. Remember, Rolex is arguably one of the most vertically integrated watch manufacture in the world, and it makes just about every component of the watch itself. One thing it does not make, however, are the hands – which come from a supplier called Fiedler SA – and crystals.

“The first thing I notice when I step inside Rolex is just how many people there are. Machines too, but mostly people.”

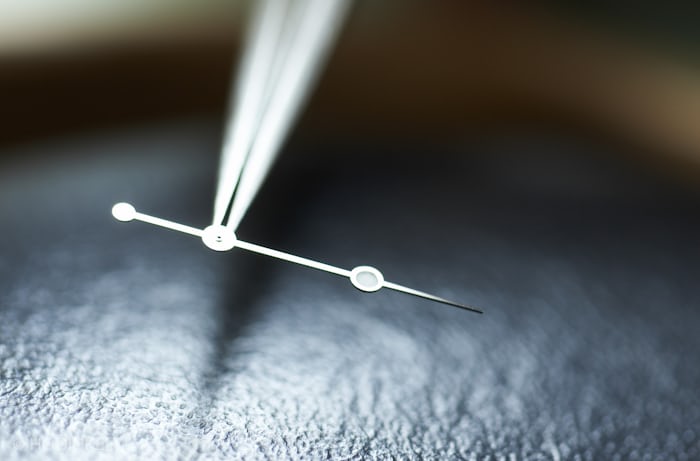

You’ll see dials and hands being set into the watch, movements being put in cases, and serial numbers being entered into a global database that allows Rolex to track the flow of each and every watch. Each group in the final assembly facility is totally autonomous, and they work on two to three month rotations. Attaching hands, for example, is a simple enough process, but ensuring that the hands rotate with the right amount of tension, are completely parallel to the dial, as well as ensuring they will clear the glass in the right way, is an arduous process. Then, after the dial is mounted, a watchmaker will take as much time as necessary to ensure there is not a single speck of dust anywhere inside the watch. One of the final steps is to replace the temporary crown of the movement placed in by COSC, and attach the self-winding rotor.

After final assembly is completed and a watch actually looks like a watch, they are turned over to final control for what can only be described as a downright shockingly intense set of tests.

It should be noted the full watches go into final control – not just movements, or cases, but entirely completed watches, as you’ll receive them. This means they have their hands on, bracelets are attached, and they are ready to wear. The three focuses of these tests are exactly what you would expect from founder Hans Wilsdorf’s three goals in watchmaking: precision, waterproofness, and self-winding.

The Oyster test submerges each watch into real-life conditions – or pressurized tanks that simulate the guaranteed depth of each model with an additional margin of 10 percent for good measure. The dive watches? They’re actually tested to an additional 25 percent margin, in a special machine designed by no one short of Rolex’s historical partner in dive-watch badassery, COMEX. Less than 0.1 percent of watches tested show any issues at all.

After the waterproofness test and self-winding module examination, the completed watches are set into boxes of 10 for a rigorous 24-hour accuracy test. But before the test begins, the watches are photographed – exactly 24 hour later the watches will be photographed again, and the two images laid upon each other. If the images do not align perfectly, the watch will be sent back for further adjustment.

This, my friends, is where things get good. Plans-les-Ouates (an industrial park outside Geneva that’s also home to, among others, Piaget, Patek Philippe, and Vacheron Constantin) is where the Rolex of our collective imagination comes to reality – complete with robotic inventory machines straight out of Star Wars, a private gold foundry, and iris scanners. Built in 2006, Rolex Plan-les-Ouates is the largest of all Rolex facilities, comprising six different wings that are 65 meters long by 30 meters wide by 30 meters high, all linked by a central axis. I should also note that everything you can see from the outside of the building is actually less than half of what Rolex has here – the complex is 11 stories high, but you can only see five from the outside. The other six are underground and completely hidden from a casual observer’s eye, or the eyes of would-be competitors.

Here there are not only no cameras allowed inside, but we are also asked to surrender our mobile phones. This facility is, in my opinion, the core of Rolex’s competitive advantage and unlike any other Swiss (German, or Japanese) watchmaking facility on the planet. It may actually be completely unique in other industries too. I’ll explain why below.

Upon entry (and surrender of all digital device), we take a small elevator a few floors underground. The doors open to reveal what looks to be something akin to Dr. Evil’s underground lair, in the best possible way. The floor is cement, the hallways are wide. Access control points are everywhere – if someone doesn’t absolutely need to be in a particular room, then they simply do not have access to it. We immediately notice a gigantic elevator door – and when I say gigantic, I mean an elevator at a scale that I’ve never seen. I inquire about it – it can hold a load of up to five tons.

We are shuffled into a secure room – we are about to see the legendary Rolex automated stock system. Our guide places his eyes to the iris scanner (no lie) the doors slide open, and what we see is downright startling. It looks like this.

Sorry guys. No photos allowed, nor provided. So what I will do is give you my best written description of what this absolutely extraordinary automated system looks like. There are two 12,000 cubic meter vaults, spliced by a network of rails totaling 1.5 kilometers, transporting over 2,800 trays of components per hour between the 60,000 storage compartments and the workshops upstairs. The view is straight out of Star Wars, minus the 1970s camp. This is efficiency defined.

There are two, 12,000 cubic meter vaults, spliced by a network of rails totaling 1.5 kilometers, transporting over 2,800 trays of components per hour between the 60,000 storage compartments and the workshops upstairs. The view is straight out of Star Wars.

Once someone within the workshops above requests a component, this incredible system takes just 6-8 minutes to retrieve it and deliver it to their work station. I remember when I was in undergraduate business school, our supply chain professional proclaimed Wal-Mart to be the model of professional logistics. I would almost guarantee you he said that because he’d never been to Rolex Plans-les-Ouates.

Rolex owns its own foundry, where it creates its very own formulas for three different kinds of gold, and its own formulation of 904L stainless steel. Every single alloy used by Rolex is produced entirely in-house because, as they are quick to point out, the composition of the metal is the most important factor in determining a watch’s aesthetic, mechanical, and dimensional properties.

Rolex is able to make these special compounds because they have invested in something that few other watch companies would even dream of: a central laboratory with world-class experts in not only materials, but also tribology – the science of friction, lubrication, and wear – chemistry, and materials physics. This laboratory was truly extraordinary to see, and what was perhaps most impressive about the lab was not only the incredible testing going on, and the machines they’ve developed themselves (for example, Rolex invented a machine to open and close an Oyster bracelet clasp 1,000 times in a matter of minutes), but also the people who work there. I was asked not to mention from where Rolex has retained many of its top-tier scientists, but you can guess, and they are 100 percent not from the watch industry.

Rolex’s ceramics department is also industry-leading, and while we only really see it used on bezels so far, the team is enthusiastic about its possibilities.

It is in this facility that I also saw something that I really never expected to see – a finishing department. Rolex does finish their watches, and expertly at that, just without the traditional aesthetic flourishes that we as consumers tend to look for when we are examining haute horlogerie, which of course, Rolex is not. Cases are held against a polish wheel by humans, just as they are at Jaeger-LeCoultre or Audemars Piguet. At any given time, there are between 50 and 60 people polishing the cases of Rolex watches. The human element in Rolex watchmaking is more than substantial and very real.

Assembling the trademark Rolex Oyster and Jubilee bracelets is also done by hand with the assistance of some very clever guide templates – made completely in-house, of course.

Our next stop was Rolex Chêne-Bourg, which is located to the northeast of Plan-les-Ouates along the border with France (but still only a short drive from Geneva proper). As I’ve said several times now, Rolex makes just about everything on its watches in its own special way – this includes dials. At Chêne-Bourg, we see all dials not only being produced, but also printed and set with indexes and other elements. The building is 10 stories in total but again, five of them are hidden underground. The production takes place underground, while the numeral application (done by hand) and gem-setting (also by hand) takes place in bright-white rooms filled with sunlight. At least 100 people are working on dial-setting at any given time.

Around 800 people work in the Chêne-Bourg Rolex facility and the work here is absolutely cutting edge. In the past, paint was applied to the dial with Scotch tape – seriously – but now it is transferred with a special silicon pad made, you guessed it, completely in-house by Rolex. All dials are made of brass, while all dial markers are solid gold, and over 60 operations must be completed before a dial is finished.

I think what was perhaps most surprising about my visit to Chene-Bourg was the quality of gemstone and setting work Rolex does. I don’t really think of Rolex producing many watches with diamonds and stones, and they admit they don’t. But, this is Rolex and if they are going to do something, they are going to do it the Rolex way. This means 20 in-house gem setters, some of whom have names like Bulgari and Cartier on their resume. The stones they use? Only IF quality – otherwise known as “internally flawless” for those not familiar with jewelry-speak.

One of the coolest things I saw here was a machine that Rolex uses to filter the stones they receive for fakes, or anything that might not be what it’s supposed to be. One assumes that any supplier of Rolex understands just how big a business it is and might be tempted to take advantage of this, perhaps by including fake diamonds in with the real stones. Yes, well, Rolex has a machine in-house that can filter stones in mass to cull out anything that isn’t a real diamond. The machine costs tens of thousands of dollars so I asked how frequently they received a stone from a supplier that wasn’t an actual diamond. The answer? About one out of 10 million. They do it anyway, because this is Rolex.

In contrast to the three Rolex manufacturing facilities in the outskirts of Geneva, Rolex Bienne is located in the Jura Mountains, north of Bern and just a stone’s throw further along the mountains from the Vallée de Joux. This region is arguably the heart of Swiss watchmaking and Bienne is the very heart of Rolex. It was, of course, up until 2004 a completely separate company owned by the Borel family of the Aegler company – hard to believe if you’re hearing it for the first time but indeed, Rolex didn’t own its own movement supplier until the Borel family sold it to Rolex Geneva in 2004, for (reportedly) over CHF 1 billion.

Despite that, there isn’t a location that is more Rolex than Bienne, and going inside here is easily the most exclusive invitation in all of watchmaking. The contents of this 92,000 square meter facility are, in the world of watchmaking, essentially priceless. This is the building everyone who loves watches, and who’s interested in Rolex, dreams of getting inside.

Let’s get one thing straight first – all Rolex calibers are completely made in-house to a degree matched by almost no other brand. Second, each movement is hand-assembled. That doesn’t mean Rolex doesn’t employ some absolutely next-level machinery to get components to a point where the watchmakers can put together the movements. Bienne does use a version of Rolex’s in-house stocking system that I mentioned earlier, though on a pared-down level. Here, I am happy to report, is an image of the Bienne system along with a look at the beautiful interior of the facility.

The reason that Rolex allows so few people into the Bienne location is because they have created a truly unique manufacturing system, for which they have built machines that create unique components exclusive to Rolex. Blanks of brass, copper, and steel are cut using proprietary machines unseen anywhere else in Switzerland, via spark erosion. Baseplates are produced at a rate of about 100 per minute. There are stripping machines where raw metal is inserted in one end, and out the other end comes full components with pins already in them.

There are stripping machines where raw metal is inserted in one end, and out the other end comes full components witih pins already in them.

There are machines in Bienne that are capable of doing the work of 100 traditional tools in a matter of 50 seconds. These we were asked to not photograph, and I am sure you understand why. It is also in Bienne that several components unseen elsewhere in watchmaking are produced. This includes the Parachrom balance spring, and the Paraflex Shock Absorber – two things that, in the opinion of many, are essential to the accuracy and durability of Rolexes.

Lets dig a bit further into these special, Rolex-only components.

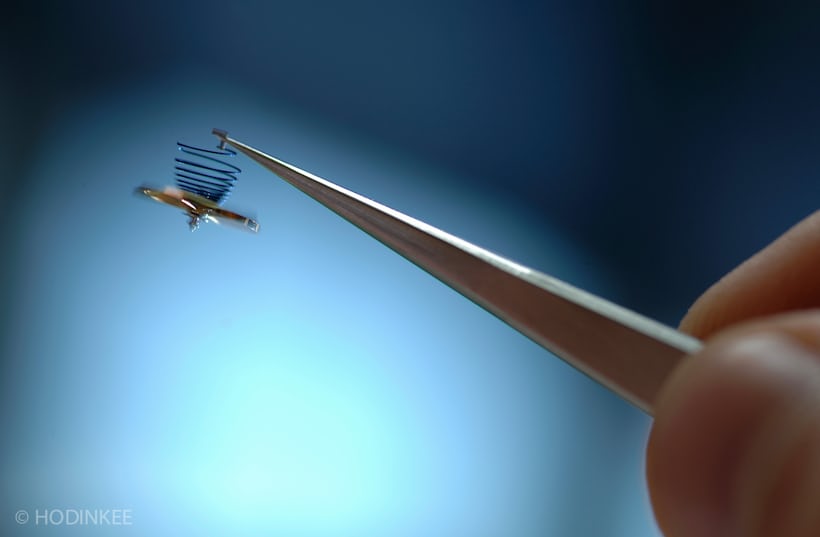

This balance spring was developed entirely by Rolex and is patented. Compose of a niobium-zirconium alloy, it can offer up to 10 times better accuracy than a traditional balance spring. It is unaffected by shocks, or magnetic fields, eliminating the need for anti-magnetic cages. The process by which the Parachrom spring is created is daunting. Tolerances are within microns, and the amount of work that goes into these springs is extraordinary. Over 120 people are required to work in this department, and each spring features a Breguet-type overcoil. The tool that makes this final curve is proprietary to Rolex, though it requires human operation.

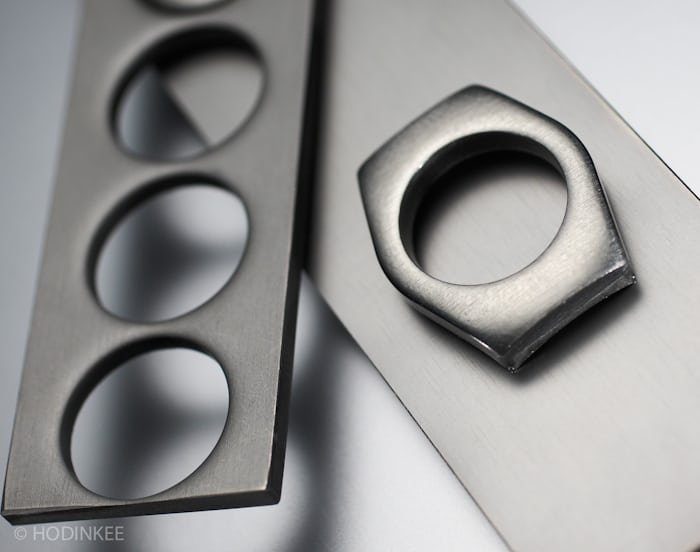

The Paraflex Shock Absorber, seen above, is an other completely new development from Rolex. After extensive work with 3-D modeling, Rolex was left with a patented innovation that improved on traditional systems by over 50 percent.

As for the actual watchmaking, there is indeed a difference between complicated and non-complicated watches. Those calibers that are considered in the elite group of Rolex production are those from the Sky-Dweller, Yacht-Masters, and Daytona. Over 120 people work on these three watches alone, with eight different cells of 15 people each. The caliber 4130, Rolex’s in-house chronograph caliber, I am told, has received numerous updates since its launch, but without much mention from Rolex, or the press. While my hosts that day don’t say specifically what has been done to the 4130 since its launch, this left me curious. Could it be that a watch company would actually spend the money and take the time to make a better product without shouting from the rooftops about it?

Could it be that a watch company would actually spend the money and take the time to make a better product without shouting from the rooftop about it?

I will come back to this below, but as Bienne was the last of the four Rolex facilities I visited, I wanted to quickly express my thoughts about what I was thinking that day. I admitted from the very beginning that I love Rolex, but prior to this trip, it was more for what the company was, and who wore them over the last 50 years, then what it is today. This changed completely, and for the first time I found myself wanting to purchase a modern Rolex. There is something so wonderful and undeniable about the purity of their mission – to create the longest lasting, most precise watches on the planet.

An Anonymous Watchmaker’s Take

As I just mentioned, Rolex PR told me that the caliber 4130 from the modern Daytona was regularly updated since its launch with little to no communication to customers. I couldn’t believe it. After all, a lot of what we do at HODINKEE is fielding press releases from brands trying to create a story where there really isn’t one. So, I reached out to a few friends at Rolex, and at competing brands, and no one knew anything. Then I spoke to a friend who is an independent watchmaker – he does not work for Rolex but does, with some regularity, work on them, in addition to watches from several other brands. He asked that he remained anonymous. Here is what he had to say:

“Setting Dufour and Voutilainen level movement finishing aside, from a pure engineering perspective, Rolex’s 3130 based calibers have reigned supreme for close to 30 years now. No mass-produced movement outside of Rolex comes close to matching their quality, durability, and reliability. They have come terribly close to defining the epitome of what a perfectly conceived mechanical watch movement should be.”

“Rolex took everything that was good about their 3130 series of movements and applied it to a chronograph. But they didn’t stop there. They also took a long, hard, critical look at how they could improve upon the design thinking behind the 3130 to make it even more reliable. They looked at the weak points of the 4030, as well, and determined how best they could improve on what they had learned from it. The result was the 4130.”

“As for improvements on the 4030, there are several. Top five, in my opinion, would be:

1. Vertical clutch 2. Modularity of automatic section 3. Full balance bridge with height adjustment nut 4. Single point of adjustment for the chronograph system (versus five in the 4030) 5. Parachrome hairspring – I believe it was there from the beginning, sans blue colour at the outset.”

“On top of that, they kept the goodness that was already in the 4030, such as the column wheel and free-sprung, microstella balance wheel (which Rolex equips all of its modern calibers with).”

“They didn’t stop with all of that, either, though. Getting back to your reason for touching base: they have quietly been improving on the design since its debut at the turn of the millennium.”

He continued: “It is not unusual for Rolex to make incremental improvements to their calibers. The 1500 series went through multiple iterations over its long history. The 3000 series received small improvements, tweaking part tolerances. All of the ladies’ calibers have also seen small improvements over the years. That’s the Rolex way. Continually improving things, down to the smallest details. The upgrades to the 4130 haven’t been mere tweaks, however, they bring notable improvements.”

“An ‘upgrade’ they did make some noise about was the blue Parachrom hairspring. As alluded to above, earlier 4130s were equipped with a white ‘Parachrom’ hairspring built on the same molecular foundation. Once proven and, in light of cutbacks from Swatch Group and its subsidiaries like Nivarox, it was important for Rolex to market this milestone in their vertical integration of production. More importantly, to me, the Parachrom hairspring was a serious horological leap forward in terms of precision and reliability of timekeeping.”

“They made a small upgrade to the train wheel bridge, modifying some of the components and the way that they operate upon it, to improve the reliability of the hour and minute counters. I would class this upgrade as being similar to the minor upgrades made to previous generations of Rolex movements.”

“A more notable upgrade that they introduced is a hairspring protection block, which eliminates any possible risk of the lower coils of the hairspring tangling in the hairspring’s overcoil when the watch endures a hard blow. To the best of my knowledge, this was a horological first. I have never seen anything like it from any other watch company. It is stunningly brilliant in its simplicity and it does its job flawlessly. While the wearer of a Daytona may never notice it’s there, they would quickly notice if it were not should the watch take a hard knock.”

“The biggest incognito upgrade are playless gears in the chronograph system. As I’m sure you already know, the vertical clutch system of the 4130 eliminates the jarring start of the second that can be noticed on chronographs that feature a lateral clutch when the chronograph is started. Playless gears take this to the next level, by eliminating backlash between gear teeth. In simple terms, backlash is a small amount of space, or ‘play,’ between the teeth of two gears that are interacting with one another, so that one tooth can disengage as another tooth moves in to continue to the transfer of energy.”

“It is stunningly brilliant in its simplicity and it does its job flawlessly.”

– – AN (ANONYMOUS) EXPERT WATCHMAKER

“A certain amount of backlash is necessary in any traditional gear system to prevent the gear train from binding and locking up. Unless the profiles of every single gear tooth are absolutely perfect (impossible), the spacing between the gears remains absolutely perfect (impossible), and there is zero play in the motion of the gears themselves (unlikely and inefficient), the tooth that is disengaging will become jammed between the tooth it is pushing and the tooth that is trailing it if there is no backlash. Thus, backlash was a necessary evil. To solve the issue, Rolex fabricates playless gears, one atom at a time, using a process known as LiGa (lithography-galvanoplasty). An additive manufacturing process. LiGa makes it possible to create gear forms that would be impossible to realize using traditional machining tools.”

“With this technology, Rolex was able to devise a gear form wherein the center of each gear tooth can be hollowed out, leaving behind two spring-like flanges that act as what would traditionally be the full tooth form. In this manner, both sides of the tooth can remain engaged with the gear it is interacting with throughout the entire duration of the tooth’s transfer of energy, taking up any necessary play (backlash) in the hollow area in the center of the tooth.”

“MB&F made some fuss about LiGa gears when they launched the HM2. That was the first time I had heard of this technology, which Jean-Marc Wiederrecht / Agenhor employed for the retrograde minutes. Little did I know then that Rolex had already rolled out this technology, in relative mass production, with the introduction of the Yacht-Master II earlier that year. After proving itself in the wild, in the Yacht-Master II, the technology was introduced as an upgrade to the Daytona several years later, bringing absolutely fluid and seamless motion to the chronograph hands as they start and reset.”

“From its inception to its present incarnation, I have yet to encounter another watch movement that comes close to matching the thoughtfulness and attention to detail so evident as in the 4130’s design.”

“In sum, Rolex’s 4130 represents the pinnacle of horological engineering. It is, arguably, the superlative in mechanical timekeeping. From its inception to its present incarnation, I have yet to encounter another watch movement that comes close to matching the thoughtfulness and attention to detail so evident in the 4130’s design.”

So, how is that for an endorsement?

Rolex Today

As I’ve said twice in this story so far, I never, not once in a million years, thought anything under the sun would make me want to own a modern Rolex. Vintage Daytonas, Subs, GMT’s, and well, everything old has so much character and charm. The way the patina on the dial shows a life lived is simply inimitable by modern Rolex. But, Rolex of today has other charms that now, after a look inside Rolex today, I can better understand, and better appreciate. For me, as something of a collector, the appeal of vintage is always there – each watch has its own personality, its own story. But vintage watches are fickle, occasionally bordering on obnoxious in the extent to which they are willing to cooperate. Modern Rolex watches tell a different story – their lives haven’t yet been lived; instead they seek to be worn every day without much attention from their owners. They are quietly superb, and by superb I mean the pinnacle of not only Swiss watchmaking, but also, I might argue, something much greater than that. To me, Rolex was Apple before Apple was Apple: the focus on simple, lasting design, innovative technology and above all else, integration into your life, not disruption.

Will I buy a modern Rolex any time soon? I might, and will I wear it a lot? I’m sure I will – Rolexes just have a way of working their way onto your wrist, no matter what else you own. I hope now those of you who have looked down on this true bastion of efficiency, design, and precision will no longer. I began by saying that “Rolex is Rolex for a reason.” Now you, I know, know much better what some of those reasons are.

For more information, visit Rolex.com.

Get More Articles Like This in Your Inbox

We're constantly creating great content like this. So, why not get it delivered directly to your inbox? By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy but you can unsubscribe at any time.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.