In-Depth: This Pièce Unique Vacheron Is Proof That Sometimes, They Do Make ‘Em Like They Used To

Made with century-old components and hundred-year old skills, the 1921 Pièce Unique is a time capsule of a timepiece.

A lot of the time, when people look at a nice watch, the words “hand made” or “hand finished” come up. But the amount of actual manual work that goes into most modern watches is deliberately kept to a minimum.

There are two reasons for this. First of all, hand assembly and hand finishing are both slower than partially or fully automated manufacturing processes, and when you’re making tens or hundreds of thousands of watches a year, they’re simply impractical.

The second reason is that they are generally less precise, and less likely to produce reliable watches, than automation. This isn’t to say that there isn’t some hand work involved – setting watch hands is often done manually or semi-manually, and there are other assembly processes, even in very large series production, that are done by humans, not robots. But for practical reasons, the watch industry has, in fact, moved as quickly away from making things by hand as possible. The enormous American watch factories run by companies like Waltham and Elgin, which produced watches by the millions, were by the late 19th century, miracles of industrialization, not craft, and European makers followed suit as quickly as they could.

Which is why Vacheron Constantin’s new unique piece is so remarkable. The Pièce Unique 1921 is an exact replica of the watch created in 1921, which was the inspiration for several models in the Historiques collection, known collectively as the American 1921 watches.

The modern versions, like virtually all luxury watches, are made using a combination of automated processes (mainplates and bridges, for instance, are cut using computer-controlled CNC machines) and hand finishing and adjustment. The Pièce Unique 1921, however, was made almost entirely by using manual techniques from the 1920s and earlier – and, moreover, with components which as much as possible came from the enormous cache of new old stock parts in Vacheron’s archives. This includes all the mobile parts of the movement (gears and pinions, as well as the balance and escapement) as well as the blued steel hands. The watch taken as a model for the Pièce Unique was made in 1921 and sold in 1928 to the Rev. S. Parks Cadman, a famous American liberal Protestant minister, who pioneered the use of radio as a way of spreading the Gospel. Cadman was at the forefront of advances in communication, and the wristwatch he bought from Vacheron Constantin on April 18, 1928, shows that his taste for innovation extended to wristwatches as well.

Cadman’s watch was and is a dare-to-be-different design. The cushion-shaped case wasn’t so out of the ordinary for the time – after the First World War ended, many watchmakers experimented with non-round case shapes. And especially before the Great Depression sobered things up globally, there was a tremendous outpouring of inventiveness in case and dial design, influenced by both the Art Nouveau and Art Deco movements. However, the Cadman watch was very unusual in having the winding and setting crown located, not at the 3:00 position on the case, but instead at 11:00. The dial was also rotated counterclockwise from its normal position, with the numeral 12 directly under the crown.

While the watches based on the original Cadman watch are all called American 1921, there is actually one earlier version of this design in Vacheron’s archives, which was completed in 1919. That model has a dial with radium-painted Arabics, and instead of having the crown to the left, it’s located at the upper right, with the dial rotated to the right as well.

This raises the interesting question of why you would put the crown in such a relatively fiddly place, and why you’d rotate the dial so the 12 is in a counterintuitive position? For quite some time the urban legend around the 1921 was that it had originally been designed as a driver’s watch. A driver’s watch is supposedly one from which the time can be read without removing your hands from the steering wheel (though presumably, back in the day, your Armstrong-Hepworth Continental Mark VIII would have had an eight-day dashboard clock) but these generally are watches with the dial set perpendicular to the movement plate, like the Parmigiani Fleurier Bugatti Type 370. On top of that, Vacheron’s heritage and style director, Christian Selmoni has said on several occasions that there is no evidence whatsoever in Vacheron’s archives to support the supposition that these were intended to be driver’s watches.

I took it for granted for many years that the 1921s were in fact driver’s watches but I suppose I should have smelled a rat sooner – five seconds of casual observation and a modicum of critical thought should have made it obvious that there’s nothing about the 1921 that makes it easier to read if you’re driving. So what gives? Well, there’s a clue in the relative position of the crown and the small seconds. Crown at the top, and small seconds at the bottom, is exactly the arrangement that you’d find in a pocket watch movement.

The movement in the watches from 1919 and 1921 was configured for casing in a pocket watch, and I think this design probably represents Vacheron exercising some creativity in designing a wristwatch around a pocket watch movement, rather than anything to do with cars. Selmoni also told us that when Vacheron decided to re-introduce the design, in 2008, they asked themselves the same question Vacheron asked in 1919-21, which was where to put the crown – ultimately, of course, they chose the configuration first used in 1921. The modern 1921 watches, by contrast to the originals, also have the sub-seconds dial offset by 90º from the crown, rather than 180º – this is because the modern versions are built around the caliber 4400 AS, which was designed from the get-go as a wristwatch movement.

Regardless of the reason, I think it’s an inspired piece of creative thinking. The easy way out would be to just put the crown in the usual position, with the seconds dial at 9:00, but by leaning into the challenge, Vacheron came up with something really arresting and interesting – a watch with a twist, as the company likes to say.

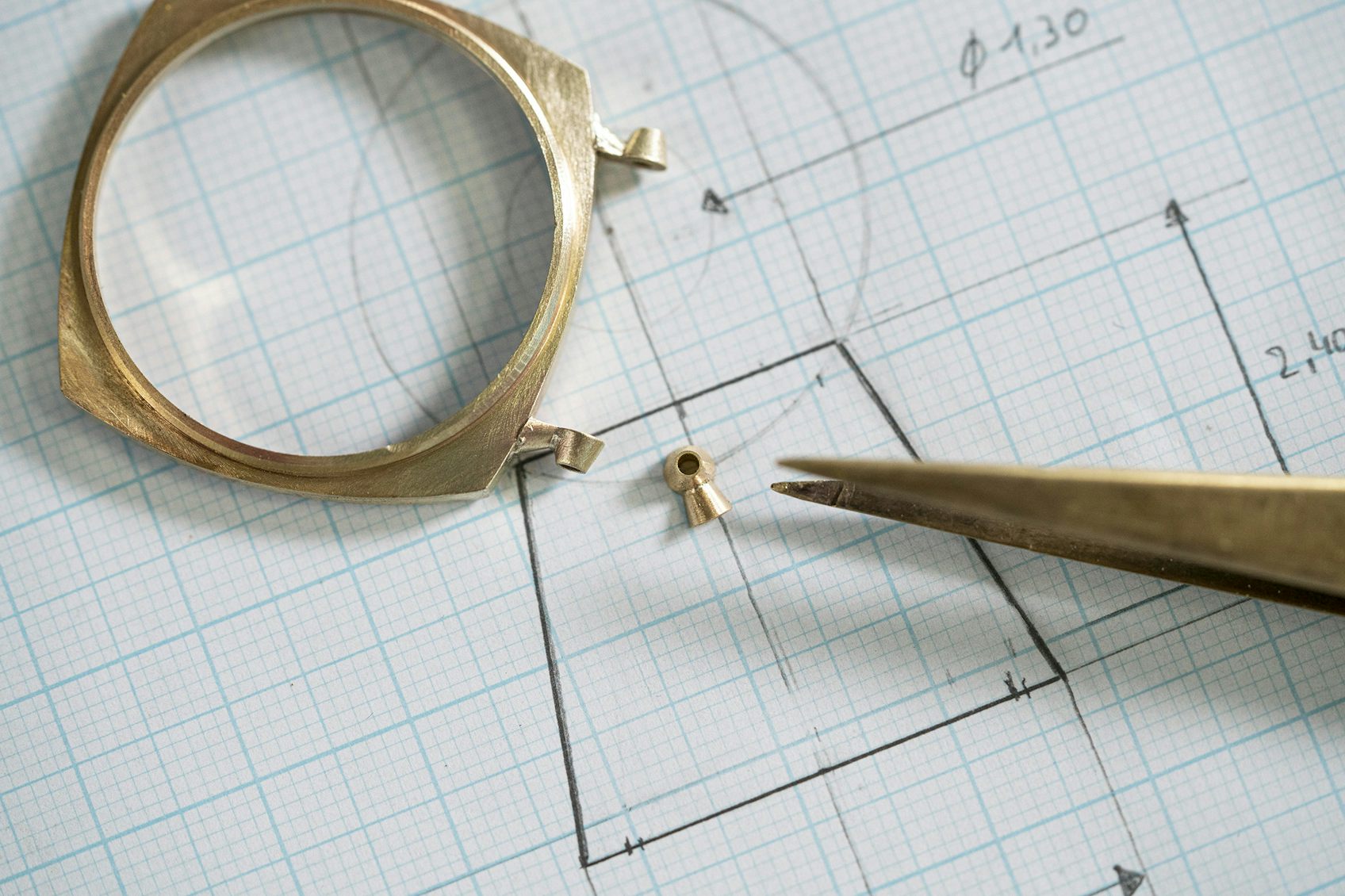

The case for the Pièce Unique is constructed as it would have been in 1921, including the soldered lugs. It’s also made of the same gold alloy as the original – Vacheron did a spectroscopic analysis of the metal in the Cadman watch and the unique piece is, like its predecessor, made of 3N 18 karat gold. Like the original, the new case has fixed bars for the strap, rather than springbars, and Vacheron used a period-correct, original crown from the early 20th century, from its archives.

While the case is not new old stock, it was made using techniques that would have been immediately familiar to a casemaker from the 1920s. Components were turned and shaped by hand and polished by hand, and the caseback engraving was done by hand as well.

Once they’re finished, the bezel, case middle, and caseback are ready to be introduced to each other, with all three turned out as carefully and beautifully as any trio of debutantes at the ball.

The dial and hands, like the case, are made using traditional techniques. The dial is fired enamel and made in two parts – the main dial, and the subdial for the small seconds. Of all the methods used in the creation of the unique piece, the fired enamel dial is probably the one most familiar to today’s enthusiasts, as enamel dialmaking, while unquestionably a high-craft technique, is used fairly often in high-end watchmaking.

For all that, it still always seems kind of magical to me. Enamel is basically a kind of glass – it starts as a powder, which gets sprinkled onto the dial in a thin, even layer. The dial is then fired in a kiln, which turns the powder into a single, thin, glossy layer in a process known as vitrification. The dial is attached to the movement with small wire pins called “feet” which are soldered into place.

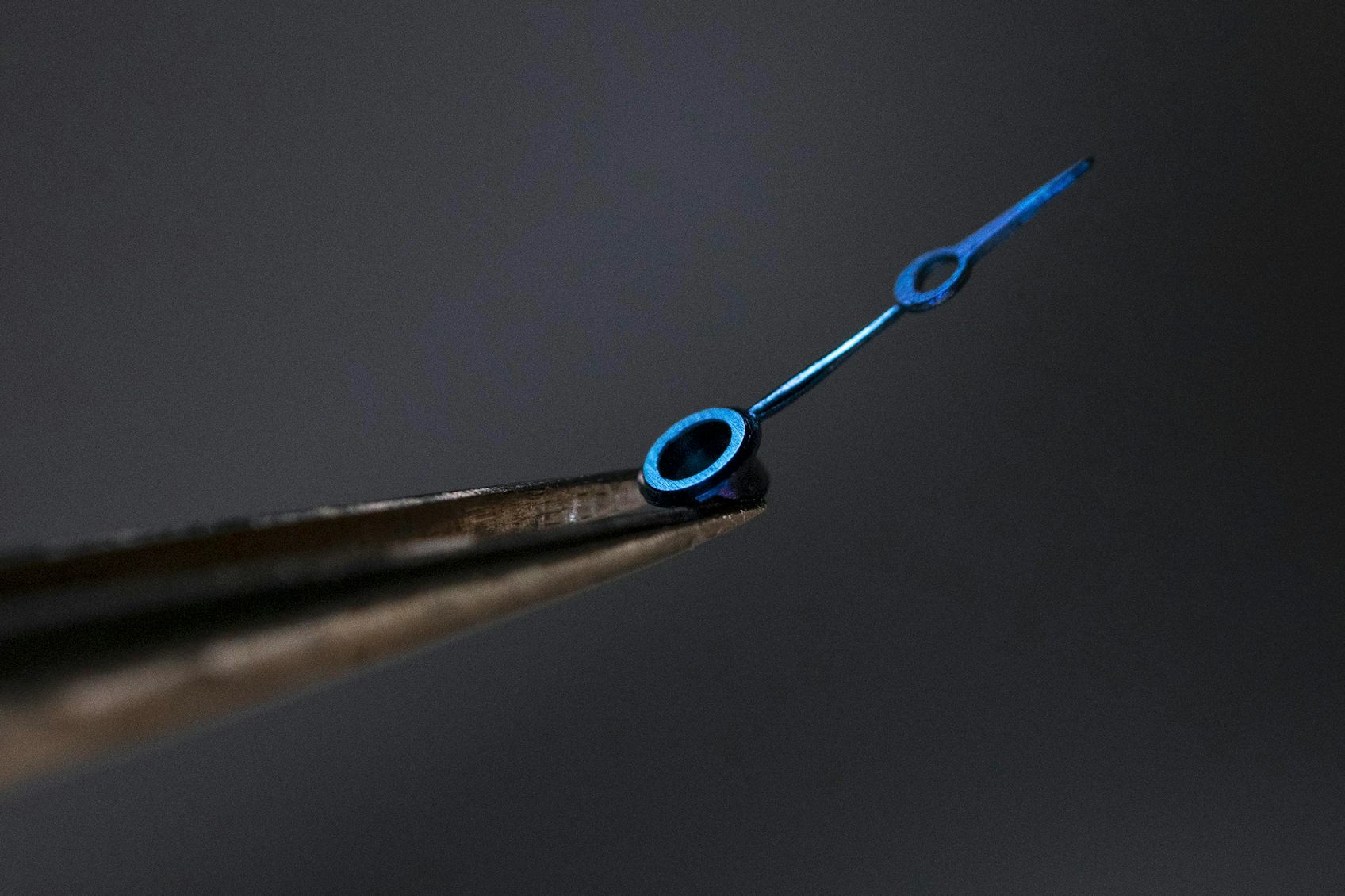

The blued steel hands, unlike the dial, are actual new old stock parts. Made in 1921, they were stored in Vacheron’s parts archive in an unblued state, and heat blued in Vacheron’s restoration workshop in 2021, specifically for this project. Heat bluing is done by placing the steel part on a block, which is then slowly heated over a gas flame. It’s a tricky process – when you heat-temper steel it begins to color at around 350º, but between 450º and 590º, it changes color rapidly, shading from a light to dark brown, to a deep purplish hue, before hitting the cornflower blue usually desired for heat blued watch hands.

One thing that hasn’t changed since the 1920s: Watch hands are still friction-fit onto their posts. The hour and minute hands are set by hand so that they’re exactly parallel, with just enough clearance between them to run without fouling each other or the small seconds hand (one of the first things I learned when I started working on vintage pocket watches was that if a watch stopped for no reason, the first thing to check was if the hands had loosened on their posts and started rubbing against each other or the dial. Sometimes on older watches, you can see arc-shaped scratches on the dial caused by loose-fitting or incorrectly set hands). I feel good for the hands on the unique piece – they had been sitting in a drawer through a depression, two World Wars, the dawn of manned space flight, the quartz crisis, the digital revolution, and the birth of the World Wide Web before finally fulfilling their destiny, but they got there in the end.

The movement – called simply a Calibre Nouveau in Vacheron’s archives – used in the original watch, is an 11 ligne (if you are wondering what a ligne is wonder no more) hand-wound movement. It’s loaded with old-fashioned charm – the main bridge is barred, rather than curved, with lovely sharp inner angles and a clean, logical, simple layout which has served fine watchmaking well ever since Lépine invented bridge movements in the mid-18th century. All the mobile components of the movement are new old stock, from the 1920s. This includes the wheels, mainspring barrel, pinions, and of course, the escapement, balance, and balance spring – a plain blued steel spring with a Breguet overcoil.

The balance is extremely exciting if you are fond of labor-intensive anachronisms – it’s a cut, bimetallic, temperature compensating balance. Today, balance springs are composed of materials that don’t change elasticity significantly when the temperature changes. Plain steel balance springs, however, become more or less stiff as the temperature falls or rises, which can cause the watch to run faster or slower. The bimetallic balance is made of two strips of laminated brass and steel, and it actually increases or decreases in diameter as the temperature changes, to compensate for changes in balance spring elasticity – hence the term, “compensating balance.”

The plates and bridges are the only parts of the entire watch that have been made with modern manufacturing methods. Both were made using German silver, and cut on a multi-axis, computer-controlled lathe. The reason for doing this was pragmatic – it was to ensure that critical dimensions were within specs necessary for smooth and reliable running of the watch. You’ll notice that there are no Geneva stripes – this is because Geneva stripes were not used on the original movement either. If you look closely, you’ll also notice that there is no antishock system on the balance pivots, which is also period-correct (albeit it means you have to handle the watch carefully – drop a pocket watch with no antishock system six inches onto a hard surface, and you’ll bend or break the balance wheel pivots).

One particular challenge Vacheron faced was setting the jewels for the balance and going train. Generally speaking, nowadays jewels are set by machine, and friction-fit into holes milled into the movement. Setting jewels by hand is a bit more involved. The dimensions are unforgiving – the ideal in watchmaking is what watchmakers call, “free but without shake,” meaning that the pivots of the gears can rotate freely, but that tolerances are tight enough that there’s no additional movement. This is one of the most basic challenges in watchmaking – a truly exact fit would produce enough friction to stop the movement, but too loose, and you have a less precise timekeeper.

For the unique piece, the jewels were first pressed into place, using a device called a staking tool. The setting of each jewel is then completed by raising the metal around it to secure it in place – a process similar to techniques used to set gemstones in jewelry. The holes for jewels in the mainplate and bridges were drilled using an 18th century upright drilling tool.

The wheels and pinions are original, archival components. “Wheel” means the larger diameter gear, and a pinion is the smaller gear on the same axis as the larger – wheels drive pinions, which means each wheel in the gear train turns faster than the one before it. The individual gear teeth in the movement were shaped and polished using an 18th century “rounding up” (or “topping”) tool. All the movement decoration, including polishing the flanks of bridges, beveling and polishing the edges, and engraving, were done by hand as well.

The result of all this effort is a watch that is, more than is usually the case in mechanical horology, a real museum of watchmaking. The degree to which Vacheron has recreated and reinvented long-dormant or even long-lost watchmaking techniques is unprecedented in watches from a modern brand – probably the closest to it would be something from an independent maker like Roger Smith, but even his watches benefit from more up to date high-precision machining methods. The 1921 Pièce Unique is almost willfully archaic – I’m not sure when the last new wristwatch with a cut balance was made, but it’s been many decades (at a guess I would say, sometime in the late 1930s or early 1940s) and a number of the techniques and tools on display in this watch, have not been seen in some cases, in close to a century.

Vacheron hasn’t decided where the Pièce Unique 1921 will eventually find a home, but to quote everyone’s favorite extremely careless archaeologist, Indiana Jones, I personally think ” … it belongs in a museum!” Wherever it does end up, however, I hope it remains possible for as many members of the watch-loving public to see it as possible. It certainly doesn’t represent the cutting edge of state-of-the-art modern horology. But to understand just how the craftsmen-scientists of an earlier era managed to produce a portable, high-precision timekeeper using largely hand-tools and hand techniques is to better appreciate how far watchmaking has come today – and to better appreciate, as well, just what the often-used term “hand made” really means.

Get More Articles Like This in Your Inbox

We're constantly creating great content like this. So, why not get it delivered directly to your inbox? By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy but you can unsubscribe at any time.