In-Depth: How Heuer, Breitling, And Hamilton Brought The Automatic Chronograph To The World 50 Years Ago

A look back at watches that changed everything, on the occasion of their shared 50th birthday.

It’s a well-known story, at least in the community of vintage watch collectors. It’s a story about one of the most important events in the history of watches.

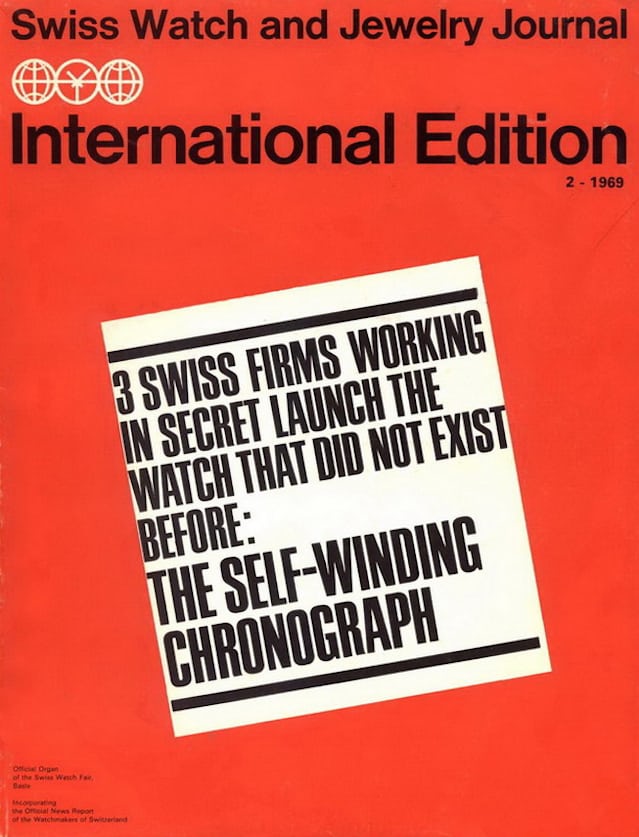

And so it has been almost obligatory for bloggers and journalists to publish narratives of the race between three watch companies (or joint ventures of watch companies) to produce the first automatic chronograph. There were three contestants – Seiko, working alone in Japan; Zenith, around the time of its acquisition of Movado; and the joint venture between the Swiss brands Heuer, Breitling, and Hamilton-Buren working with movement specialist Dubois-Depraz.

Oddly enough, to this day, there are three winners of the race, depending on how the “race” is defined. In January 1969, Zenith publicly introduced a prototype of its automatic chronograph, although it appears that the first “El Primero” chronographs were sold to customers only in Fall 1969. Seiko enthusiasts point to codes on case-backs to suggest that the Reference 6139 chronograph was produced in March 1969, however, these watches were sold only in Japan and it appears that retail sales outside Japan began in 1970.

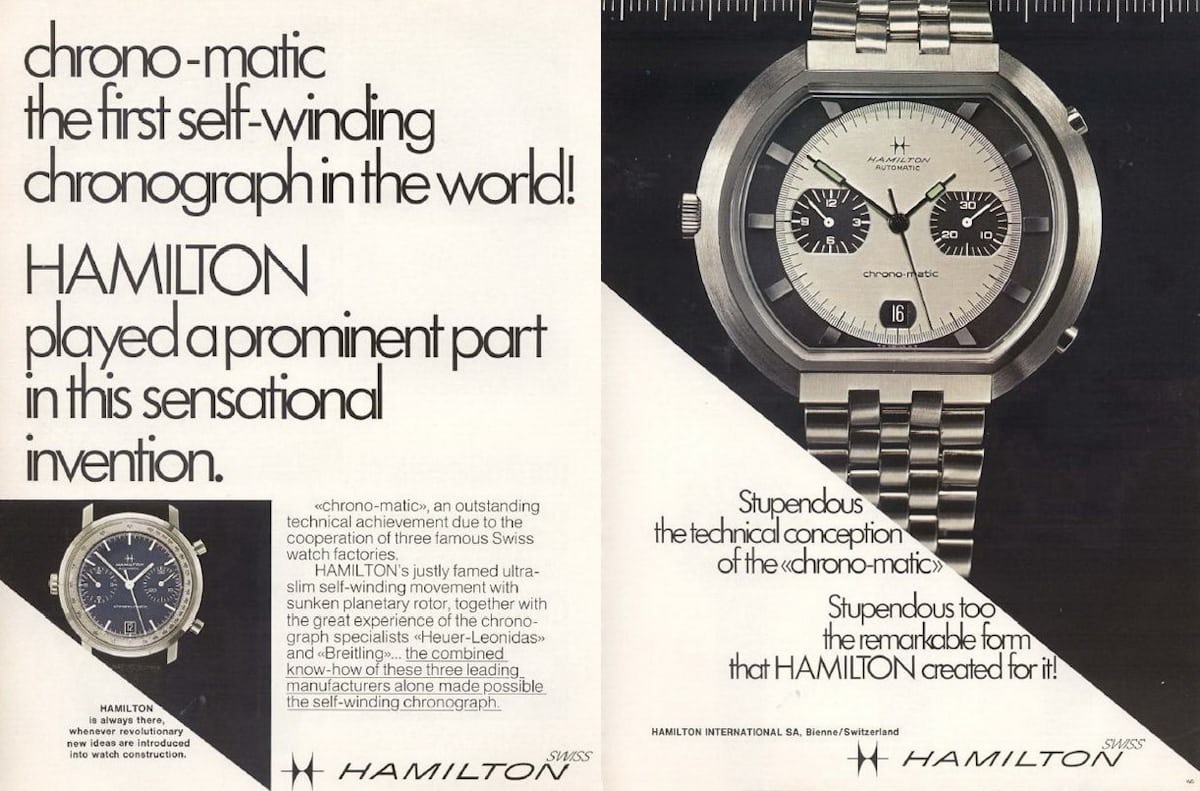

Heuer, Breitling and Hamilton introduced their new “Chronomatic” watches at press conferences held on March 3, 1969, simultaneously at 5:00 PM in Geneva and 11:00 AM in New York City.

In early April 1969, the three brands showed their watches at the Basel Watch Fair, together having at least 100 samples to share with the media and their retailers. Store receipts from July and August 1969 establish that customers were able to buy the new Chronomatic watches by the Summer of 1969.

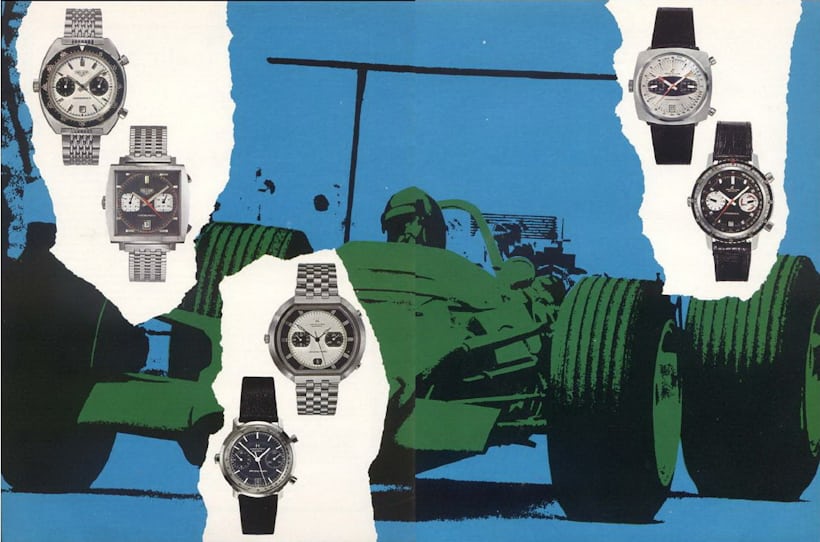

In this posting, rather than recapping the race, we will explore this chapter of watch history from a different perspective. We will look at the portfolio of 23 automatic chronographs offered by Heuer, Breitling and Hamilton when the watches were first available in retail channels around the world, during the summer of 1969. Watch collectors often view history and catalogs with a narrow focus on their favored brand. In this instance, a look across the Heuer, Breitling and Hamilton Chronomatic catalogs shows a rich and varied selection of watches, with each of the models best understood in the context of the models offered by the other brands.

Additionally, we will explore the origins of the Chronomatic designs. We tend to think of the Chronomatic family of watches as embodying the style of the 1970s, and in fact that’s when most of these watches were sold. A closer review of the Heuer, Breitling and Hamilton portfolios confirms that the style of these watches was deeply rooted in the design revolution of the “Swinging Sixties”.

Project 99

To understand the automatic chronographs that Heuer, Breitling and Hamilton offered in the summer of 1969, we begin with the roles of the partners in their joint venture to develop the world’s first automatic chronographs (called “Project 99”). When the popularity of automatic watches being sold by its competitors began to cut into the sales of its chronographs (all of which were manually wound), Heuer embarked on the project to develop the automatic chronograph.

First, Heuer enlisted Buren, a skilled maker of watch movements, that had developed the thin micro-rotors that seemed promising to power the new chronographs.

Next, Dubois-Depraz joined the team. An experienced designer and producer of modules providing complications for watches and timers, Dubois-Depraz would develop the chronograph module that would be mated with the Buren watch movement. Hamilton ended up with a seat at the table, when it acquired Buren, in 1966.

In his autobiography, Jack Heuer explains how Breitling came to be a member of the Project 99 joint venture. Faced with the enormous cost of developing the new movement, and short of capital for its own business, Heuer viewed Breitling as a deep pocket that could supply funding for the project. Though Heuer and Breitling were rivals, the fact that Heuer was stronger in the United States, the United Kingdom and Germany, while Breitling was stronger in France and Italy, would mitigate the competitive impact of the collaboration. Still, we must imagine that Heuer was desperate for capital when it invited Breitling to join the venture.

Project 99 resulted in the development of the Caliber 11 movement (referred to, with its successor models, as the “Chronomatic” movement). The Caliber 11 movement employed modular construction, mating Buren’s micro-rotor powered watch movement with a chronograph module developed by Dubois Depraz. Watches powered by the Chronomatic movements are easily recognized – the crown is on the left side of the watch, with the pushers in the usual positions on the right side. The Caliber 11 has its hour recorder at nine o’clock, its minute recorder at three o’clock, and a date window at six o’clock, with no running seconds register.

The Caliber 11 movement uses 17 jewels and Incabloc shock-protection. The movement measures 13.75 ligne, with a diameter of 31mm and a height of 7.7mm. The frequency was 19,800 vibrations per hour, with a power reserve of 42 hours. In the Caliber 12 movement, the frequency was changed to 21,600 vibrations per hour; the Caliber 15 movement used a KIF shock protection system.

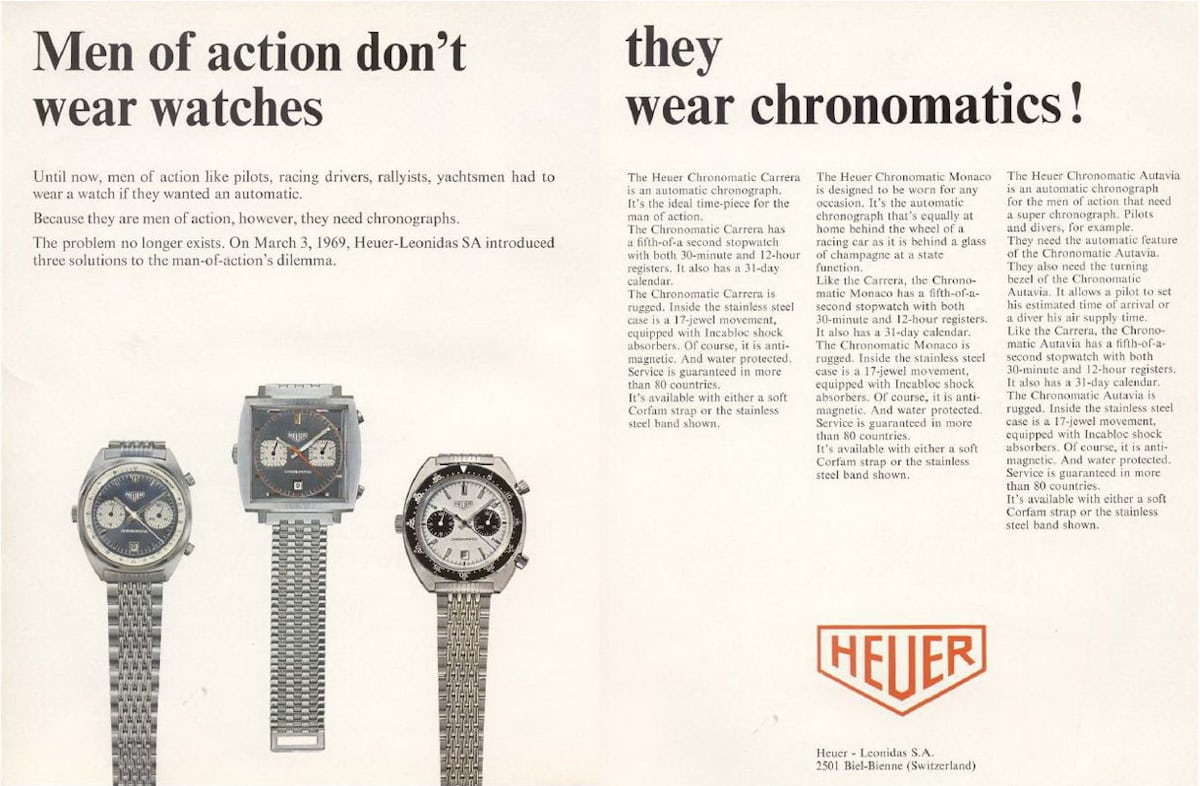

The Heuer Chronomatics

In the mid-1960s, Heuer’s line-up of chronographs consisted of its two flagship models, the Autavia (introduced in 1962) and the Carrera (introduced in 1963), as well as a variety of other less expensive models, known only by their reference numbers. Heuer’s third named model, the Camaro, would be introduced in 1968.

As Heuer began to plan for the addition of automatic chronograph models by the end of the decade, the company took the approach of continuing to market its catalog of manual-winding models, in their current configurations. The new Chronomatic models would be added to the catalog as premium models, being sold alongside the previous models.

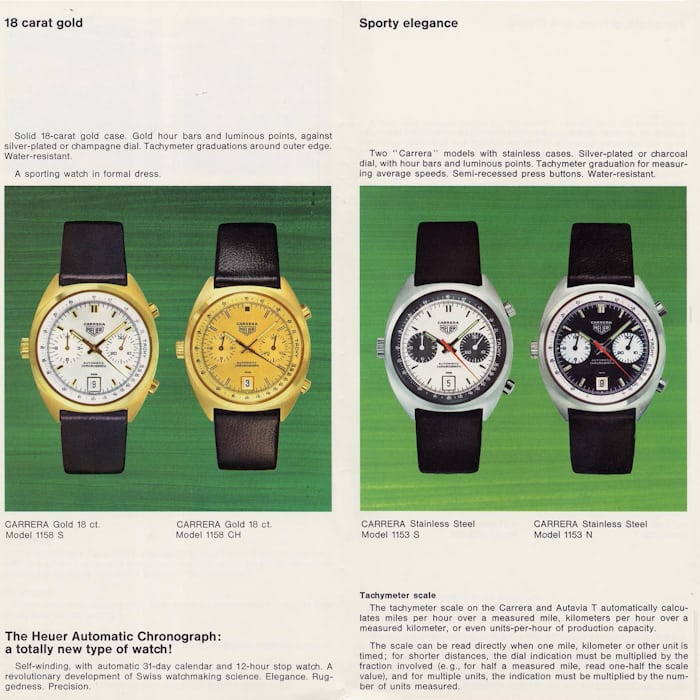

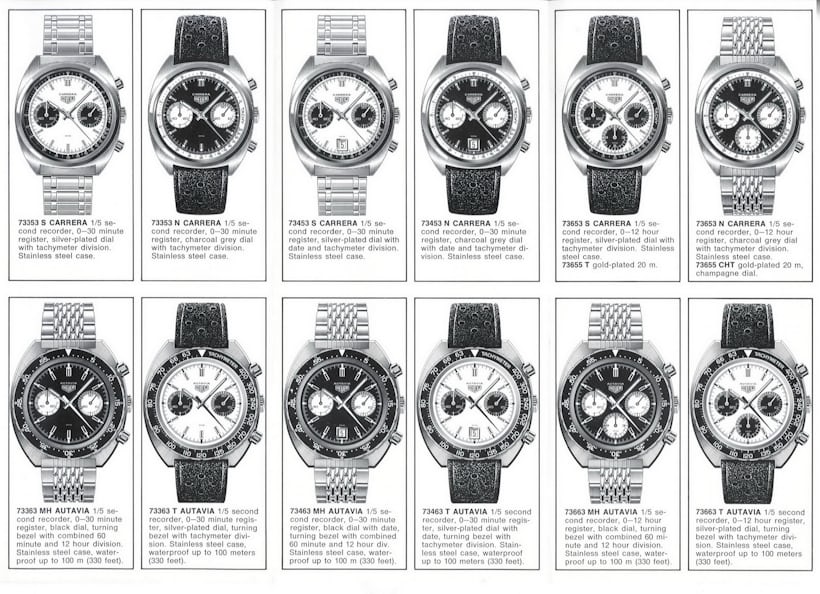

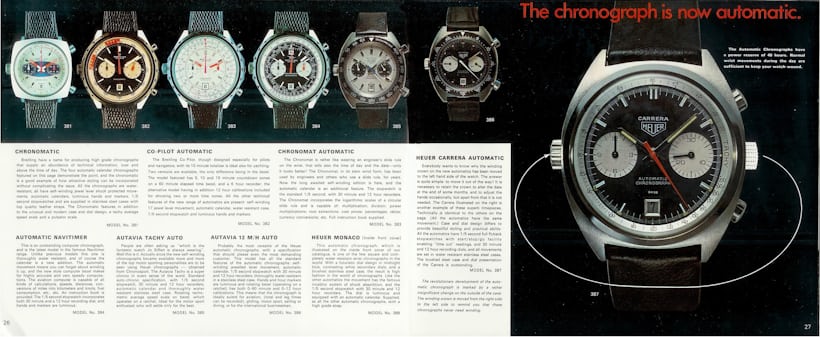

Manual Carreras from the 1960s used traditional round cases, with distinctive angular lugs. Dials were either black or white, but from there, the variety of Carreras increases quickly. The registers were either matching or contrasting; there were tachymeter, decimal minutes and pulsations scales; calendar options included a simple date as well as triple calendar (day, date and month); and materials included stainless steel and 18 karat and gold-plated models.

Heuer turned to its favored casemaker Piquerez to design the new case for the Chronomatic Carrera. Rather than drawing an entirely new style of case for the Carrera, Piquerez produced a natural extension of a case that had been draw by Gerald Genta, for the Omega Constellation, in 1964. In Genta’s revolutionary “C-Shape” case, the lugs, rather than being extensions of the case, flow in a continuous arc from the crown, providing a C-shape from lug-to-lug. The C-shape case proved to be popular in the late 1960s, being used by several brands for watches and also enlarged to house a variety of manual chronograph movements (for example, Omega’s Caliber 321 and Eterna’s Valjoux 72). For the new version of the Carrera, Piquerez built a thicker style C-shape case, though the designers exercised restraint in keeping the size (38.5mm) toward the minimum that could house the new movement.

There were two versions of the Chronomatic Carrera – a stainless steel model with a charcoal / blue dial and white registers and an 18 karat gold model with a silver dial. A version with a silver dial and contrasting dark registers soon followed, though the dial is marked “Automatic Chronograph”, rather than “Chronomatic”. Dials of the new Carreras were relatively clean, with a tachymeter scale marked on an inner bezel between the dial and the crystal.

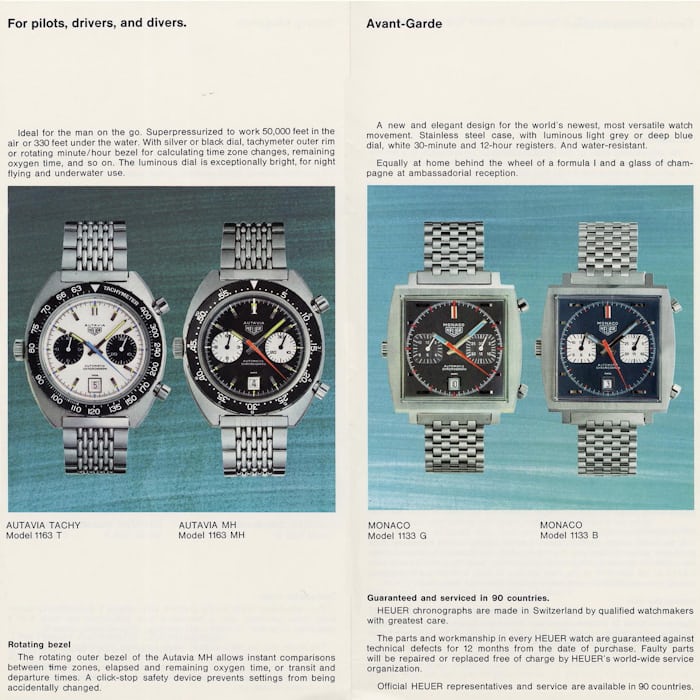

Since its introduction in 1962, defining features of the Autavia model were black dials with white registers, with a rotating bezel that was marked for different functions (diving, travel, tachymeter, etc.), and these features were carried forward to the new Chronomatic Autavias (Reference 1163 MH). Piquerez had designed a C-shape case for the new Carrera, and would produce a second version for the Autavia, this larger case (42mm) incorporating the Autavia’s signature rotating bezel.

Through its first seven years, Autavias had always used a black dial with white registers, but to mark the development of the Chronomatic Autavia, Heuer would offer a second color scheme – a white dial with contrasting black registers and blue accents (Reference 1163T). This white-dialed model was worn by Swiss Formula One hero, Jo Siffert, and to this day the Autavias with the white / black / blue colors are known as the “Sifferts.”

As described below, in 1966 and 1967 Piquerez had designed waterproof watch cases for Hamilton in radical oval and square shapes. Heuer wanted something special for its third automatic chronograph model, and it appears that Piquerez had saved the best of its cutting-edge designs for this loyal customer, a design that – for the first time – would house a chronograph in a square, waterproof case. The key to the design of the Monaco case was a unique monocoque case and bezel, that were held together by internal clips.

Freed from the constraints of having any model predecessors, the Chronomatic Monacos used a midnight blue dial with contrasting white registers, the paint on the early versions having a brushed metallic finish. A charcoal gray version of the Monaco with matching registers would soon join the Heuer line-up, though the dial would be marked “Automatic Chronograph”, rather than “Chronomatic.”

Identifying the first Heuer chronographs to use the Caliber 11 movement is easy – the very first models all have the name “Chronomatic” across the top of the dial, with the model name across the bottom of the dial. At the time Heuer introduced the Chronomatics, the United States was the most important market for the company, and Heuer learned quickly that Americans struggled to understand that the word “Chronomatic” meant “automatic chronograph”. Accordingly, almost immediately after their launch, Heuer removed the “Chronomatic” from the dial, and for the next 15 years all Heuer models using the Caliber 11 movement (and its progeny) would have the words “Automatic Chronograph” across the bottom of the dial, with the model name across the top.

After launching the “Chronomatic” versions of the Autavia, Carrera and Monaco in 1969, circa 1971 Heuer developed manual-winding versions of these models, housed in the same style cases as the automatics.

Heuer significantly expanded the line of Caliber 12-powered chronographs in 1972, with its introduction of the outrageously styled (and sized) Calculator, Montreal and Silverstone models. The third generation of Caliber 12 models came circa 1977, with the Cortina, Daytona, Jarama, Kentucky, Monza and Verona models all showing a more restrained, traditional design.

Heuer continued offering the Caliber 12 powered models into the mid-1980s.

The Breitling Chronomatics

While Heuer took the approach of continuing to sell its 1960s manual chronographs alongside its new automatic models (circa 1969), with new cases for the manual models coming some years later (circa 1971), Breitling took a very different approach. As soon as Breitling knew the dimensions of the new Caliber 11 movement (which we can assume was circa 1966), it developed new cases for its portfolio of manual models, with the new cases being designed so that they could be easily adapted to house the new automatic models. Thus, Breitling made the move from its traditional round cases of the 1950s and early 1960s to the new generation of larger cases that would house the Chronomatic movements, not in 1969, but beginning in 1966 / 1967.

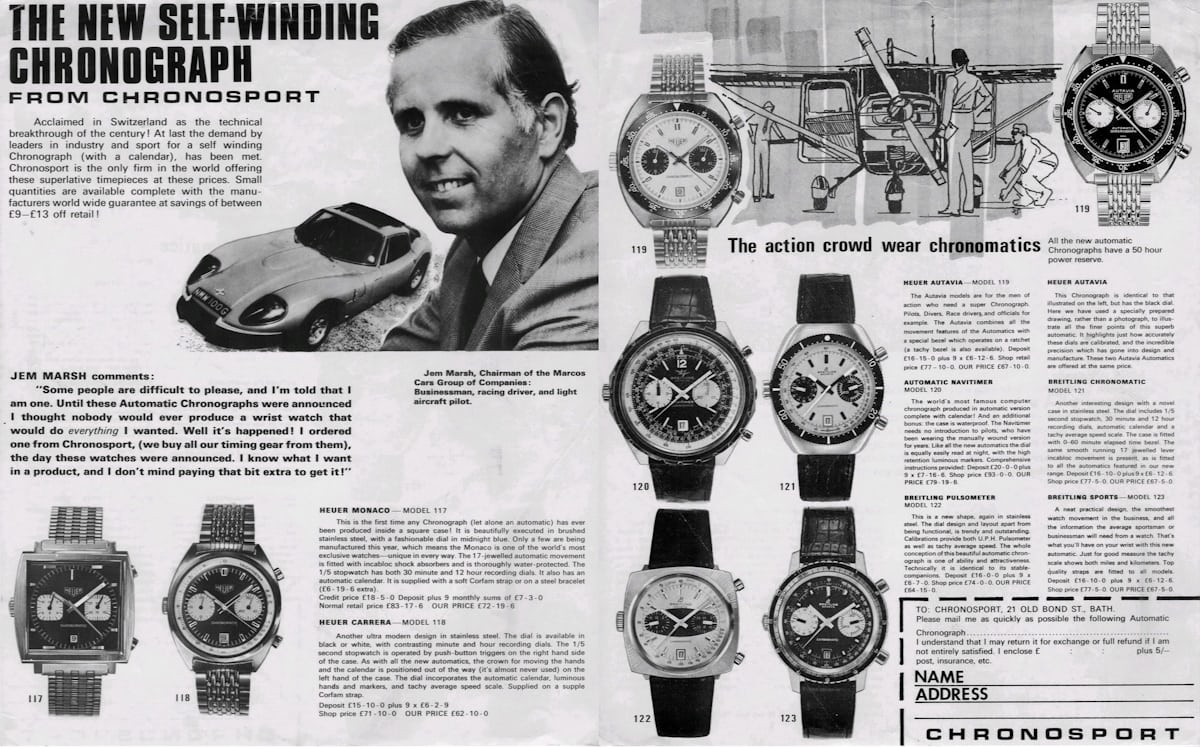

Catalogs and advertisements from the period confirm that Breitling launched its line of automatic chronographs with five distinctive cases, as follows:

Traditional round case with a rotating bezel and angular lugs

Pillow-shaped case

Tonneau-shaped case

- 18 karat gold case

Breitling’s distinctive six-sided case, often described as a “pizza” case, which was used for several different references

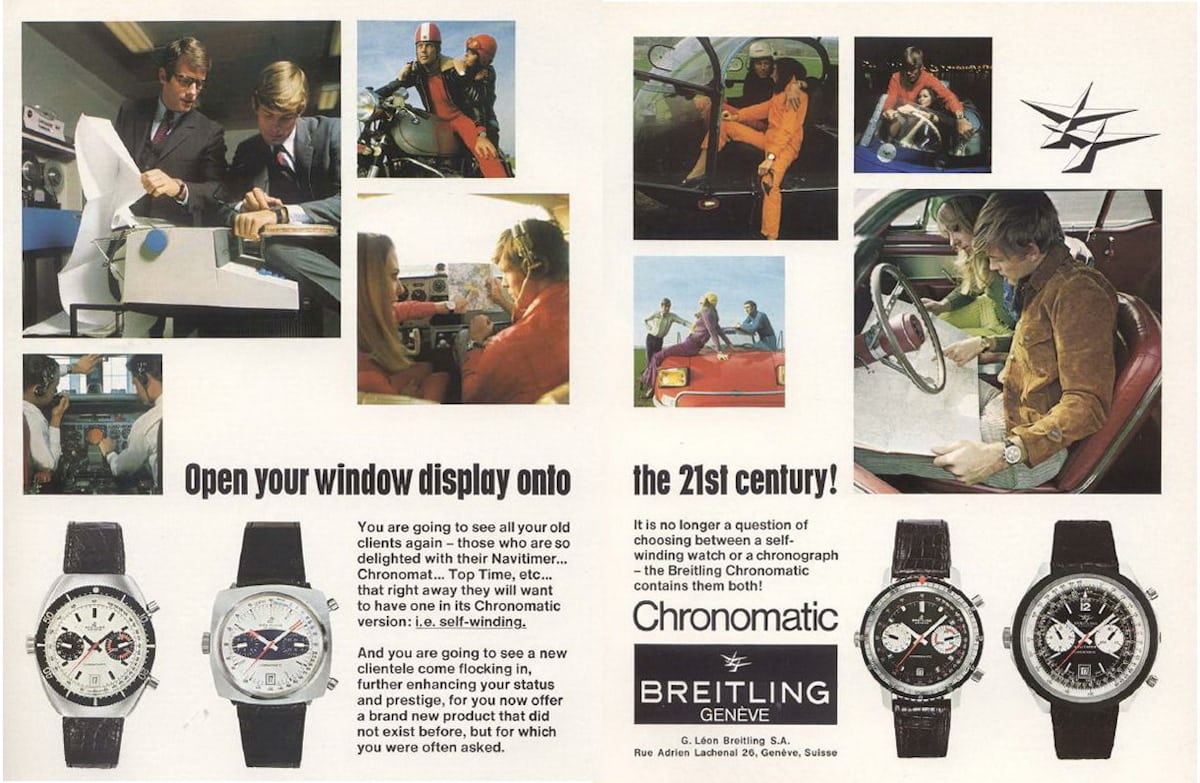

The Reference 2110 employed a traditional round case (38mm), with a rotating bezel and angular lugs. Dials were either black with white registers or white with black registers, all marked with a tachymeter scale. The hour recorders were marked with all 12 numerals and the minute recorder featured bright racing stripes, making it easier to read five minute increments.

If the Reference 2110 was the tamest of Breitling’s Chronomatics, we begin moving up the curve from mild to wild with the Reference 2111. The 38mm cushion case is a softly-rounded square shape and relatively flat across the top surface of the watch, however, the sides of the case show deep, dramatic curves. The dials are either black or white, each with a contrasting white or blue “surfboard” placed horizontally across the center, with the oblong registers situated within the surfboard.

Having gone from a traditional round case and then to a symmetrical cushion case, with the Reference 2112 Breitling stretched the steel – literally – to offer a tonneau-shaped case. A black bezel frames the dial, with the hour bezel and minutes bezel rotating. The dials and hands offer a look that is similar to the Reference 2110 models, with the watches having black or white dials (both with contrasting registers), and orange hands and accents.

The Reference 2114 was generally similar to the Reference 2112, except that the Reference 2114 had a fixed tachymeter bezel, with the tachymeter scale deleted from the dial.

Of all the cases to ever house a Breitling Chronomatic movement, the hexagon-shaped case used for several of the first models in 1969 is surely the most distinctive. Sometimes described as the “fried egg” or the “pizza”, these 48mm cases had been introduced by Breitling in April 1967, then being powered by the manual-winding Venus 178 movement. In anticipation of the development of the Chronomatic movement, with its crown at nine o’clock, the cases were constructed so that the crown could be positioned at either three o’clock (for the manual movement) or at nine o’clock (for the automatic movement).

At the launch of the Chronomatic movement in 1969, Breitling’s hexagon case housed at least five different versions of the Chronomatic, with a sixth model shown in the 1969 catalog, but never seen in the execution shown in the catalog.

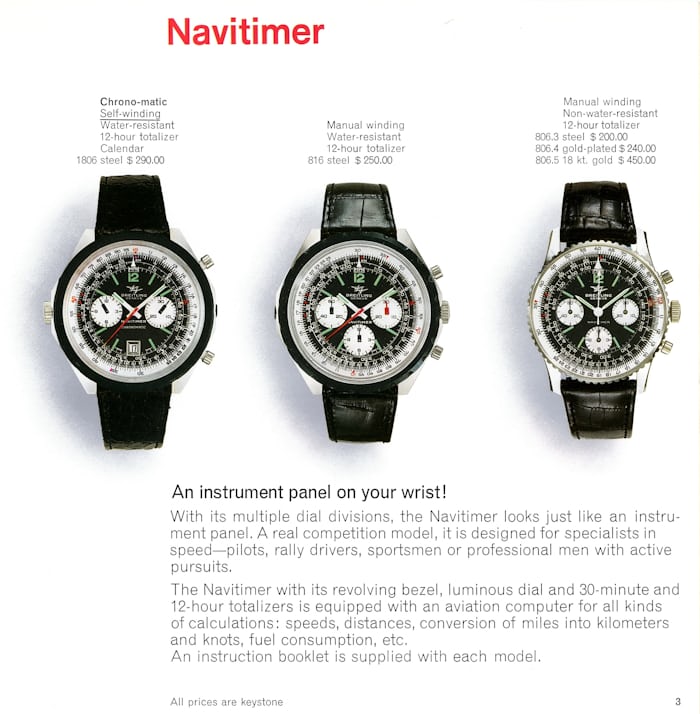

The white or black-dialed Chronomat (Reference 1808) had its origins in 1940, when Breitling offered its first chronograph incorporating the logarithmic slide rule scales into the bezel and dial, as well as a scale on the dial for decimal minutes computations. Breitling catalogs suggest that the Chronomat models are ideally suited for the mathematicians, engineers and businessmen, as well as sports and industrial timing.

The Navitimer (Reference 1806) was a continuation of the series of aviation chronographs that Breitling had introduced in 1954. For the Navitimer, Breitling modified the Chronomat’s logarithmic slide rule to a pilot’s time-speed distance flight computer, and added scales used by pilots to calculate fuel consumptions, average speeds and climbing speeds. Breitling suggested that the Navitimer was designed for specialists in speed – not only pilots, but also rally drivers and other sportsmen.

The Cosmonaute (Reference 1809) incorporated the same pilot’s tools as the Navitimer, with the watch having true 24 indication, meaning that the hour hand made one revolution per day. The Reference 809 Cosmonaute had been introduced in 1962 and become the first Swiss wristwatch in space when it was worn by astronaut Scott Carpenter on May 24, 1962.

The fourth and fifth Chronomatic models to be housed in the “pizza” cases were the Reference 7651 models. The Reference 7651 Co-Pilot model was a continuation of the series of chronographs introduced by Breitling in 1953, with the minute recorder marked to count the 15 minutes for the pilot’s pre-flight check. While all other Chronomatic watches introduced in 1969 had recorders for 12 hours, the Reference 7651 had six-hour capacity. The “Yachting” version of the Reference 7651 featured a rotating bezel that was marked in red and white segments, to count down the 15 minutes to the start of a yacht race.

Breitling’s 1969 catalog also showed a Reference 2115 GMT model in the “pizza” case, but this model seems to have only been introduced later, in a different color scheme.

The last of Breitling’s first generation of Chronomatics was the Reference 2116, a limited run of 100 watches housed in a traditionally shaped 18 karat gold case. The champagne dial had contrasting black registers and tachymeter and pulsation scales.

As described above, identifying the very first Heuers to use the Caliber 11 movement is easy – we simply look for the word “Chronomatic” on the dial or certain other telltales, after Heuer switched to the “Automatic Chronograph” dials. Recognizing the earliest Breitling Chronomatics proves to be more challenging. First, whereas Heuer used the name “Chronomatic” only on the earliest of its Caliber 11 watches, Breitling continued to use “Chronomatic” throughout the production of most of the models. So it requires some careful analysis, and the use of serial numbers, to identify Breitling’s earliest automatic chronographs. Second, the Breitling catalog of Chronomatic models offered a considerably broader selection of watches than the Heuer catalog, so the sheer variety of early models can make it difficult to track the models.

After the launch of the first Chronomatics, Breitling turned its attention to fully developing its line-up of these automatic chronographs. Colorful new models to occupy the “pizza” case included the Chrono-Matic GMT (Reference 2115), which was introduced in 1970, and the SuperOcean (Reference 2105), a dive watch with a 20 ATM waterproof rating, from 1971 (shown above).

New cases included the Pult “Bullhead” (Reference 2117, above center), and the TransOcean (Reference 2119, above left), an almost-round case with an integrated bracelet. The introduction of the Caliber 15 movement in 1972 led to a series of funky, asymmetrical dials (above right), while Breitling tipped its hat to more conservative styles with new versions of the Navitimers and Chronomats in traditional round cases.

The last model launched by Breitling, in 1977, was the Reference 2130, at first glance similar to the first Reference 2110 models, but with elegant lyre-shaped (twisted) lugs.

The Hamilton Chronomatics

In its first advertisement for the Chronomatics, Hamilton states that its ultra-slim self-winding movement with a sunken planetary rotor made the self-winding chronograph possible.

As difficult as it may be to catalog the variety of Caliber 11 watches offered by Heuer and Breitling, the line-up of Hamilton Chronomatics was relatively simple. Advertisements from Spring 1969 suggest that Hamilton offered a choice of three automatic chronographs, using two different cases. These models were produced by Heuer, for Hamilton, perhaps part of the joint venture agreement for Project 99.

Just as Heuer and Breitling offered a range of Chronomatic models ranging from quiet, traditional cases of the Heuer Carrera and the Breitling Reference 2110 to the outrageous shapes and sizes of the Heuer Monaco and Breitling’s “pizza” cases, Hamilton offered the customer seeking the futuristic style its Fountainbleau watch. Hamilton had introduced its line of Fontainebleau watches in 1966, with a line-up of stylish watches for both men and women. The first version of the Fontainbleau (from 1966) was a unique oblong shape that defies description (but we will give it a try below). The second version (from 1967) was a square, waterproof case, that could be viewed as a predecessor of the Heuer Monaco.

With the Fontainebleau chronograph, Hamilton loaded a Caliber 11 movement into the first of these two cases. Describing the shape of the Fontainebleau case is difficult (or as an engineering friend of mine said, “I can give you the mathematical formula, but the words are more difficult”). But let’s give it a try.

Start with a large round stainless steel case (47mm across the dial). Slice off the top and bottom areas of the circle with horizontal chords (which will provide a place for the strap to attach). Drop a round dial with a brushed gray finish into the center of the watch, then add contrasting black registers that mimic the shape of the case, with a similarly-shaped date window at the bottom of the dial. As a final tribute to this excess of geometric forms, fill the space between the dial and the case with a black flange, to provide a platform for 10 applied hour markers. Examine the back of the case, and the weirdness continues – monocoque construction, with the movement accessed by turning a bayonet fitting 90 degrees.

Hamilton must have exhausted its inventory of geometric tricks with the Fontainebleau, and the design of its Chrono-Matic models could hardly have been any simpler.

The Chrono-Matics used a traditional round case with angular lugs, in a relatively small size (36.5mm), making it the smallest of the watches powered by the Caliber 11 movement. Color combinations included a white dial with contrasting black registers (and a matching inner bezel) or a model with a blue dial and registers. Both these models have an inner bezel (tension ring) with a tachymeter scale, with the bezel contrasting with the color of the dial.

Hamilton introduced its Chronomatic models with only three models, but soon added to this line-up. The Pan-Europ 703 chronograph had a rotating bezel, in the style of the Heuer Autavia, and was also produced in a GMT model, with a 24-hour bezel and an additional GMT hand. Hamilton’s massive Chrono-Matic Count-Down offered both GMT and world time complications, with three crowns on the right side of the case (the additional two being for rotating inner bezels) and two pushers, for the chronograph, on the left side of the case.

Buying Them – 1969

Considered together, the automatic chronographs being sold by Heuer, Breitling and Hamilton during the Summer of 1969 offered watch enthusiasts a rich selection of choices. Those wanting “mild” automatic chronographs may have tended toward the Heuer Carrera or the Hamilton Chrono-Matic, while those seeking “wild” could have a variety of toppings on their Breitling “pizzas”, the geometric puzzle called the Fontainebleau or the daring shape and colors of Heuer’s Monaco.

Considered together, Heuer, Breitling and Hamilton enjoyed worldwide distribution, so that these models were available in a wide range of retail stores, as well as specialists (for example, catalog companies that catered to racers, pilots or engineers). In considering which companies “won the race” to offer the first automatic chronographs, if the measure is availability of a broad selection of chronographs in retail channels around the world, then there is no doubt that the Project 99 team finished first.

Collecting Them – 2019

Just as Heuer, Breitling and Hamilton offered a varied selection of automatic chronographs in 1969, fifty years later the vintage watch enthusiast seeking one of these “first batch” models is presented with a range of choices, at different price points. Entry-level choices under $4,000 might include the Heuer Carreras, Hamilton Fontainebleau or Chrono-Matics, or the Breitling Reference 2110 / 2111 / 2112 models. The middle of the pack ($4,000 to $12,000) might include either of the Breitling Reference 7651s (co-pilot or yachting) or a Reference 1163 Autavia with either a black or white dial (and “Automatic Chronograph” on the dial). The collector browsing at the top of the Caliber 11 pyramid (over $12,000) – and who is blessed with patience for a long search – could aim for the Heuers with the name “Chronomatic” on the dial or the 18 karat gold models from Heuer or Breitling.

The Revolution

Watch enthusiasts have celebrated the revolution that the automatic chronograph brought to the world of watches and, to this day, most luxury chronographs continue to be powered by automatic movements. But in these same years that the Project 99 team was laboring on the technical aspects of the new movement, the three brands – Heuer, Breitling and Hamilton – were orchestrating a revolution in the design of their new automatic chronographs.

Faced with quartz watches, the 1970s would bring enormous challenges and set-backs for these brands, and for all makers of mechanical watches. Still, with the launch of the Chronomatics in the summer of 1969, Heuer, Breitling and Hamilton celebrated the best style of the Swinging Sixties.

Visit OnTheDash for a comprehensive bibliography about the Chronomatics and remember to check out #Chronomatic50 on Instagram to see hundreds of examples of incredible Chronomatic watches too!

Writer’s Note: Thanks to @WatchFred for providing images and information for this posting, as well as inspiration to Breitling and its vintage enthusiasts.

Get More Articles Like This in Your Inbox

We're constantly creating great content like this. So, why not get it delivered directly to your inbox? By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy but you can unsubscribe at any time.