In-Depth: Blancpain’s Six Masterpieces

In the ’80s, Blancpain committed to understated, traditional, and above all, complicated watchmaking. The results are timeless.

Today, we’re telling the story of Blancpain’s rebirth in the 1980s thanks to a special set of Blancpain’s Six Masterpieces being offered by the dealer Watch Brothers London.

“Since 1735 there has never been a quartz Blancpain watch. And there never will be.”

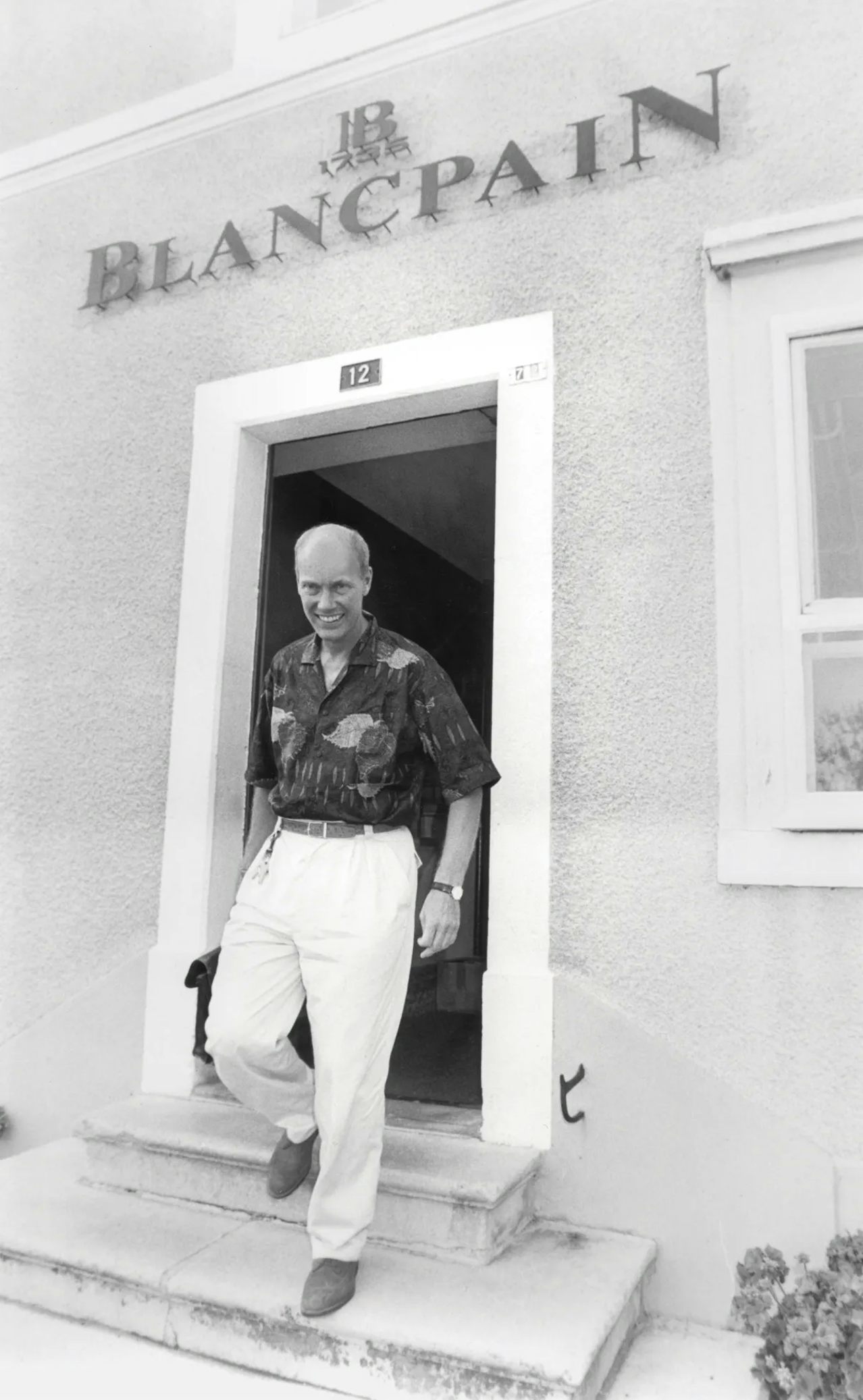

When Jean-Claude Biver and his partner, Jacques Piguet, acquired Blancpain for CHF 21,500 in 1981, this was the now-famous slogan they introduced. They were positioning Blancpain, a watchmaker mostly dormant since the quartz crisis, as a traditional anecdote to those fancy new quartz watches. Just 11 years later, Biver sold Blancpain to the Swatch Group for CHF 60 million.

While this era of Blancpain is often told mostly as a story of marketing genius thanks to Biver and those catchy slogans, there was also some real watchmaking. Biver’s partner, Piguet, was the son of ebauche maker Frédéric Piguet. Together, Piguet and Biver put together a plan to create what we now call Blancpain’s “six masterpieces.” These were six mechanical watches with complications harkening back to the days of traditional Swiss watchmaking, days that many thought might never return after the quartz crisis: a complete calendar moonphase, ultra-thin, perpetual calendar, minute repeater, split-seconds chronograph, and flying tourbillon. All six masterpieces came in traditional, round, 34mm cases, and you’ll see them engraved with their production number on the caseback.

As Biver told us in his Talking Watches, Blancpain first introduced the complete calendar moonphase in 1983. The ultra-thin ref. 0021 came the next year. By the end of the decade, Blancpain had introduced all six masterpieces. Biver, of course, kept No. 00 in platinum of each of these masterpieces – he showed us a few of them in that episode.

So once you’ve created all the complications you wanted to, what do you do next? Combine them all, of course. At the end of 1990, Blancpain introduced its Grand Complication 1735. It featured an ultra-thin movement, perpetual calendar, moonphase, split-seconds chronograph, tourbillon, and minute repeater.

To celebrate the six masterpieces and the combining of them all in a grand comp, in 1991, Blancpain presented all six individual masterpieces in a limited-edition box set: 99 sets in all, with each of the six masterpieces in platinum, all delivered in an ornate checkerboard box. In many ways, it’s the pinnacle of the Biver era of Blancpain. The next year, Blancpain sold to the Swatch Group. Now, Watch Brothers London has found set No. 1 of 99. It’s a cool piece of Blancpain and watchmaking history and gives us a chance to take a closer look at Blancpain and the six masterpieces, a period that’s only just beginning to be appreciated by collectors again.

Behind The Six Masterpieces

Sure, Biver was a marketing genius, even prone to making up stories about quartz watches. “One day, I received a letter from the Fédération Horlogère,” Biver told Europa Star in 2019, “reproaching me for having said at a meeting that quartz was carcinogenic, dangerous because of its batteries.” But behind the fibs, Biver and Piguet also had a vision of traditional watchmaking for Blancpain.

“I didn’t want to relaunch Blancpain solely with hours and minutes watches. They had to have the traditional sobriety, beautiful finishes, but also additional features. A moonphase was an ideal indicator infused with nostalgia and poetry,” Biver said. In the attic of Frédéric Piguet, Biver said they found everything they needed to make a complete calendar and moonphase movement, tools that had gone unused since the 1940s. With that, Blancpain was off and running.

Blancpain introduced the complete calendar moonphase ref. 6595 (34mm) in 1983. Alongside, it also introduced the 26mm ref. 6395, which set a record as the smallest complete calendar moonphase. Small, thin, and with that Mona Lisa smile moonphase at 6 o’clock, it made a statement about what the new Blancpain was here to do: Complicated, traditional watchmaking – and it wasn’t going to shout about it either. The type of high-end watchmaking that quartz just couldn’t match. For perspective, the ref. 6595 was introduced the same year Swatch hit the market.

By the way, many of the images here show the most conservative of the masterpieces – white dial, no gems, no fuss. But for most of these references, there are dozens of variations: mother-of-pearl dials, gemset bezels, pink-on-pink examples, all the types of rare and beautiful things that can send collectors into rabbit holes and years of searching.

Two Blancpain Ultra-thins in platinum, the second skeletonized. Images: Courtesy of Antiquorum

The next year, Blancpain introduced the second masterpiece, Ultra-thin ref. 0021. It employed the well-known F. Piguet caliber 21 first used by Piguet clients in 1925. Measuring just 1.75mm thick, it had held the record for the thinnest caliber for two decades. The ref. 0021 can be found in a number of different case metals and configurations – the most captivating are the skeletonized versions, almost a complication within a complication. Blancpain would also introduce the Ultra-thin ref. 0071, an automatic variant to the ref. 0021.

It’s simple and elegant, and while it might not be the most exciting of the masterpieces, it certainly makes a statement about the new Blancpain.

Next in 1986 came the perpetual calendar ref. Ref. 5395. Like the other masterpieces, it was small, measuring just 34mm x 9mm thick. With its three subdials and moonphase at 6 o’clock, the dial is beautiful and symmetrical and, to me, puts the watch alongside the ultra-thin QPs introduced by the big boys around the same time (for a fraction of the price, might I add). It’s even got a stepped case and short, curved lugs that make those other QPs wear so well. The first version had no leap year indicator, but Blancpain soon addressed that with the upgraded ref. 5495, which otherwise looks similar.

Now we get to the really romantic stuff: the minute repeater. Répétition Minutes, as the ref. 0033 simply declares on the dial. According to Blancpain, developing the caliber 33 for its fourth masterpiece took more than 10,000 hours. Introduced in 1988, it was one of the smallest minute repeaters yet, measuring just 3.3mm thick. Soon after, Blancpain introduced an automatic minute repeater too (ref. 0035). Blancpain couldn’t help itself, and about a year after introducing its automatic minute repeater, it combined the complication with its perpetual calendar module to create its minute repeater perpetual calendar ref. 5335.

During this era, Blancpain’s minute repeaters featured cases from Jean-Pierre Hagmann, the legendary casemaker who also made Patek’s minute repeater cases. Nowadays, he’s working with Rexhep Rexhepi to craft his Chronometre Contemporain cases.

Finally, the chronographs. In 1989, Blancpain introduced its chronograph ref. 1185, featuring the F. Piguet caliber 1185. A vertical clutch, column wheel chronograph, it was the thinnest automatic chronograph caliber until Bulgari recently introduced the Octo Finnissimo Chronograph GMT Automatic. Audemars Piguet used the movement to create its first Royal Oak Chronograph; Vacheron did the same for its Overseas Chronograph. It was just that good. But for Blancpain, it wasn’t enough – it also added a split-seconds mechanism to the caliber 1185, making the world’s first automatic split-seconds movement (caliber 1186). And the watch was still just 34mm x 6.75 thick.

Blancpain split-seconds 1186 in pink gold and platinum. Images: Courtesy of Antiquorum and Loupe This.

As it did with some of its other complication modules, Blancpain would soon add its chronographs to other complications like with the chronograph perpetual calendar ref. 5585, the split-seconds perpetual calendar ref. 5581.

In 1989, Blancpain introduced the last of its six masterpieces, the flying tourbillon ref. 0023. It was the first flying tourbillon in a wristwatch, developed with the help of independent watchmaker Vincent Calabrese. Oh, and it was still just 8mm thick.

In his Talking Watches episode, Bill Higgins – the man who collects watches in pairs – showed two versions of this Blancpain tourbillon. While the first had a traditional look, the second featured a rare “military” dial. As with some of the other Blancpain masterpieces, you can also find rare gemset versions of the flying tourbillon. Again, it’s finding these rare variations that can make learning about and collecting this era of Blancpain so fun – it’s a lot more than boring and conservative dressy watches.

Collecting Biver-era Blancpain

Together, it’s impressive what Blancpain accomplished during this decade. It helped kick off a rebirth in traditional, mechanical watchmaking. It made the first wristwatch flying tourbillon, the first split-seconds automatic chronograph, and the thinnest automatic chronograph. Then, it put this all together in a grand complication – a lot of grand comps are big and ugly or try too hard, but the 1735 isn’t and doesn’t.

Nowadays, this era of Blancpain sits firmly in the so-called “neo-vintage” category. Much of the collector interest in this category comes from an appreciation for the first era of independent watchmakers that struck out on their own – Daniel Roth, Franck Muller, Roger Dubuis, and others. Hell, we’ve taken the last couple “Vintage Watches” columns to tell you about 1990s Roger Dubuis and Michel Parmigiani’s Parmigiaini Fleurier.

Some will critique this era of Blancpain for being a little too boring or traditional, but that’s kind of the point. For example, ’90s Breguet has ornate guilloche dials, coin-edge bezels, and a watchmaking connection to Daniel Roth. Blancpain has none of this. But if simple (not easy), Swiss watchmaking is your thing like it is my thing, Blancpain might have something for you.

Perhaps because of this, ’80s and ’90s Blancpain hasn’t quite taken off the way other neo-vintage watches have. Interest among enthusiasts has increased more than prices have – people are curious about the era of Blancpain, but perhaps not to the point of actually buying one. For example, a platinum perpetual calendar originally retailed for about $30,000 just 30 years ago, and while prices have risen over the past few years – from $6,000 to $14,000 to $20,000 – they also sold for more just a decade ago.

Meanwhile, one of those six masterpiece sets retailed for CHF 385,000 in 1991 (and for that price, Biver himself might’ve even delivered it to you, as he told us in Talking Watches). There was no way these would ever maintain that type of value – and really, there wasn’t that expectation when you were buying watches in the ’90s anyway. Resale values have always been a fraction of that original retail price (CHF 75,000 in 2011; €75,000 in 2018). Now, there’s been a slight uptick in interest, with Watch Brothers London finding set No. 1 of 99 and asking £115,000 (about $125,000).

The original masterpieces are great – as a collector, I’d pay particular attention to the perpetual calendar, split-seconds chronograph, and minute repeaters. And masterpiece set No. 1 is a piece of watchmaking history, even if for that kind of cash I might put together my own personal masterpiece set. Because for me, this era of Blancpain is really fun when we get to the even more complicated stuff, where Blancpain combines perpetual calendars with chronographs or minute repeaters just because it can.

This is the type of complicated watchmaking that brands like Patek and only a few others could match during the time. If a six-figure Patek perpetual calendar chronograph 3970 or split-seconds 5004 is out of your grasp, you might look to Blancpain. The Blancpain chronograph QP ref. 5585 and split-seconds QP ref. 5581 offer tremendous value for the sheer amount of watchmaking inside. There’s even a minute repeating perpetual calendar (ref. 5335); for the money, it’s hard to think of a better way to get into chiming watches (Bel Canto aside, of course).

An interesting two-tone and a pink gold Blancpain split-seconds perpetual calendar 5581. Images: Courtesy of Antiquorum and Christie’s

Even today, these Blancpain split seconds perpetual calendars are selling for about $15,000 in gold or $25,000 for platinum. That’s an awful lot of watch for the money, and something only a few brands outside of Patek have even tried to do in the past thirty years. Or, you can pick up a minute repeating QP (again, with a JHP case!) for around 20 grand (here and here, for example; and really, only a little bit more in platinum). These were selling for more in 2008! For something similar with Patek on the dial (ref. 3974), you’ve got to add at least add a zero to that number.

Minute repeater perpetual calendar in gold and platinum. Images: Courtesy of Loupe This and Christie’s

As things get complicated, they also get rarer. While the ultra-thins are pretty easy to find and really not that exciting, some have estimated only 450 perpetual calendar chronographs were made during this era of Blancpain across all metals. You can bet there are fewer split seconds or minute repeating QPs.

This era of Blancpain is about as traditional as it gets – small round cases, old-school complications, and a partnership between a movement maker and a businessman. And while it’s mostly known as a story of marketing – “since 1735 there has never been a quartz Blancpain watch” – look beyond the catchy slogans and there’s more than enough watchmaking to back it all up.

As we explained a few weeks ago, we’ll continue to use our Wednesday Vintage Watches column to tell the stories of watches we love. Sometimes (like this week), they won’t even be Hodinkee’s watches – they’re just cool watches we’ve seen for sale elsewhere that we want to feature, kind of like the old Bring A Loupe column. If you like that Blancpain six masterpieces set, check it out at Watch Brothers London (we have absolutely zero commercial relationship with them).

Get More Articles Like This in Your Inbox

We're constantly creating great content like this. So, why not get it delivered directly to your inbox? By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy but you can unsubscribe at any time.